When Stability Comes from Abroad

Commentary

Introduction

Some of the most important financial flows in the global economy move without contracts, policy mandates, or market pricing. They are not governed by trade agreements, capital controls, or investor confidence. Yet, every month, they cross borders with striking consistency, driven not by profit, but by obligation.

These flows are remittances.

In their simplest form, remittances are income earned abroad and sent home by migrants to support households. In economic analysis, remittances are often pushed to the background, recorded under secondary income and viewed mainly as a social transfer rather than an economic driver. That framing made sense when remittance flows were relatively small, uneven, and played a limited role in the wider economy. Today, with remittances larger, more stable, and more influential, that framing may be considered less appropriate.

Over the past two decades, remittances have expanded steadily, outlasting cycles that disrupted almost every other external flow. They have persisted through recessions, financial crises, pandemics, and natural disasters. In many economies, remittances now rival exports, finance a meaningful share of imports, and supply foreign exchange precisely when domestic activity weakens. Unlike exports, they are generated outside of the domestic economy. Unlike capital flows, they do not reverse when risk arises. Their stability challenges how external resilience is typically understood. So, what exactly are the implications when a large and increasingly reliable share of economic stability depends on external income flows shaped by conditions and policy decisions beyond domestic control?

Nowhere is this question more relevant than in the Caribbean. Small domestic markets, limited diversification, and repeated exposure to external shocks mean that volatility is embedded in the region’s economic structure. In this context, remittances have emerged as a critical stabilizing force. They arrive when tourism contracts, when fiscal space narrows, and when shocks erode domestic incomes. Their growing importance suggests that macroeconomic stability in the Caribbean may increasingly depend not on what is produced at home, but on income earned abroad and is therefore influenced by external economic conditions.

The Scale of Remittances:

Globally, remittances have emerged as one of the largest and most stable sources of external financing for developing economies. Unlike capital flows or foreign direct investment, remittances have continued to expand during periods of global stress, emphasizing their resilience to cyclical downturns. In 2024, according to the Migration Data Portal, global remittance flows are estimated to have increased by 4.6% rising from USD865bn in 2023, to USD905bn in 2024, reflecting continued expansion despite slower global growth.

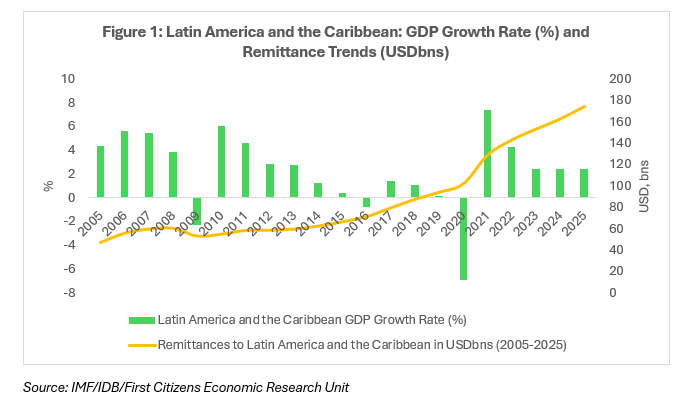

A similar pattern is evident across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). According to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), remittances to the region continued the growth path observed over nearly two decades in 2024. Inflows expanded in nominal terms even as growth rates normalized from the exceptionally strong post-pandemic surge, reinforcing the persistence of remittances as a core external inflow.

This trend has persisted amid moderating economic activity. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that GDP growth in LAC will slow to 2.4% in both 2024 and 2025, ease further to 2.2% in 2026, and strengthen modestly to 2.7% in 2027. The divergence between moderating GDP growth and sustained remittance inflows highlights the extent to which remittances have become increasingly detached from domestic economic performance.

Importantly, a moderation in growth does not imply weakening inflows. On the contrary, the IDB projects that by the end of 2025, remittances received by LAC will reach a new nominal peak, marking sixteen consecutive years of uninterrupted growth. Total inflows are expected to reach USD174.4bn in 2025, representing an increase of USD11.7bn relative to USD162.7bn in 2024.

Remittances in the Caribbean Region:

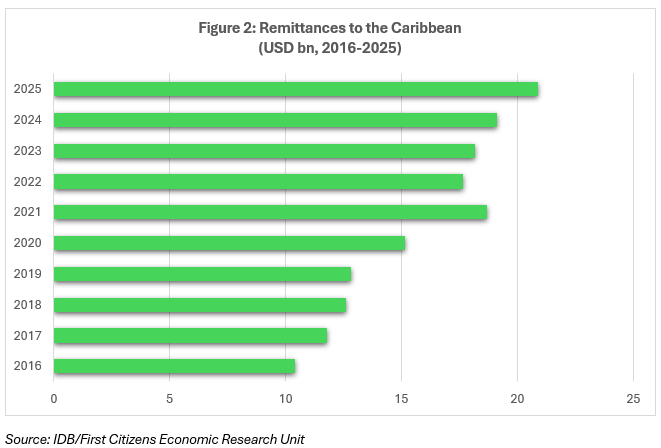

In the Caribbean, remittances have moved well beyond a supplementary role and have become a central economic variable. In 2025, inflows to the region recorded strong momentum, expanding by 9.1% in the first quarter (Q1), 7.5% in Q2, and 10.5% in Q3. This performance was driven primarily by sustained inflows to the Dominican Republic (DR) and Jamaica, alongside rising transfers to Haiti, particularly from the United States (US).

For the year as a whole, remittances to the Caribbean region are estimated at approximately USD20.8bn (Figure 2), representing a 9.2% year-on-year (y-o-y) increase, well above the 5.2% recorded in 2024. This places the region at roughly 12% of total remittances received by LAC, a share that has remained broadly stable in recent years despite shifts in regional growth dynamics.

The structure of these inflows highlights a high degree of geographic concentration. The US remains the dominant source of remittances to the Caribbean, accounting for 50.4% of total inflows. At the country level, reliance on the US is even more pronounced, with 84.5% of remittances to the Dominican Republic (DR), 62.8% to Haiti, 61% to Jamaica, and 57.7% to Trinidad and Tobago (T&T). Canada represents a meaningful but secondary source, contributing 10.2% of total inflows, with particular importance for T&T (21.2%), Jamaica (8.6%), and Haiti (10.6%), though it does little to offset overall US dominance.

In several Caribbean economies, remittances account for double-digit shares of GDP and represent a significant source of foreign exchange in highly import-dependent economies. At this scale, remittances extend beyond a household-level transfer and take on macroeconomic relevance by helping to sustain consumption and support foreign exchange currency availability. While remittances do not directly finance imports, they help ease external pressures by supporting the foreign exchange needed to maintain import flows, particularly when domestic production and export receipts are limited.

This stabilising role becomes most visible during periods of economic stress. Shocks such as Hurricane Melissa in Jamaica in late October 2025 tend to weaken tourism receipts and disrupt domestic income, increasing pressure on external balances. In these circumstances, remittance inflows often rise or remain resilient, helping to cushion the impact on households and foreign exchange availability. Given that Jamaica accounts for approximately 17% of total remittances to the Caribbean, according to the IDB, shock-related movements in remittances can influence not only national outcomes but regional aggregates as well.

A New Policy Shock: The US Remittance Tax

The growing macroeconomic importance of remittances makes recent policy developments in the US particularly relevant. Effective 1 January 2026, a 1% excise tax will be applied to certain remittance transfers originating from the US and sent through cash-based channels. The measure forms part of the One Big Beautiful Act, which was signed into US law on 4July 2025.

The tax is levied on the transaction itself and is charged directly by the remittance service provider or financial institution, with proceeds remitted to the US Department of the Treasury. Importantly, the levy increases the total cost of sending remittances but does not reduce the amount ultimately received by the beneficiary.

Transfers conducted through digital or banking channels are exempt from the tax. In response to the policy change, several remittance providers have begun adjusting their product offerings. For example, Western Union has introduced card-based options that allow users to load funds while remaining outside the scope of the 1% levy.

While the headline rate may appear modest, the introduction of a transaction-based tax has the potential to influence remittance behaviour in economies where inflows play a critical macroeconomic role.

Potential Implications of the US 1% Tax:

Early evidence suggests that even modest increases in remittance costs can have a measurable impact on transfer volumes. According to a blog published by the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB), empirical estimates indicate that for every 1% increase in remittance costs, the value of remittances declines by approximately 1.6%. Applying this elasticity to the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) implies a potential annual reduction of around USD2.36mn in remittance inflows, with the largest effects concentrated in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada and St. Lucia.

The potential scale of the impact becomes clearer when applied to larger remittance corridors. According to analysis cited in the Inter-American Law Review, Mexico, the largest recipient of remittances from the US, receives approximately 40.5% of US sourced remittance flows, amounting to roughly USD62.5bn. Under the new tax, Mexico could experience an annual reduction in inflows exceeding USD1.5bn, assuming a material share of these transfers remain cash-based and subject to the levy. For smaller economies such as Honduras, Nicaragua, and Guatemala, where remittances exceed 20% of GDP, the macroeconomic consequences could be even more pronounced, amplifying vulnerabilities in consumption, external balances, and poverty outcomes.

Beyond volume effects, higher transaction costs may alter remittance behaviour, encouraging a shift away from formal channels toward informal mechanisms or digital alternatives such as cryptocurrency. This could weaken transparency and complicate financial-integrity efforts. While the aggregate impact remains uncertain, any sustained moderation in inflows is likely to be felt most acutely by lower-income households, sharpening challenges related to financial inclusion and domestic affordability in remittance-dependent economies.

Conclusion

Remittances have become an integral part of the Caribbean’s economic framework, supporting households, easing foreign exchange pressures, and cushioning repeated shocks. Their scale and persistence now place them alongside traditional macroeconomic variables rather than on the margins of economic analysis. However, this stability is shaped beyond domestic control. Recent policy changes in remittance-sending countries highlight how external decisions can affect flows that many Caribbean economies rely on. The challenge ahead is not reducing reliance on remittances but managing it effectively. Lower costs, stronger use of digital channels and less reliance on cash, and deeper financial inclusion can help ensure that remittances continue to support resilience rather than introduce new vulnerabilities.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment, or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.