Caribbean Trade and Logistics

Commentary

Introduction

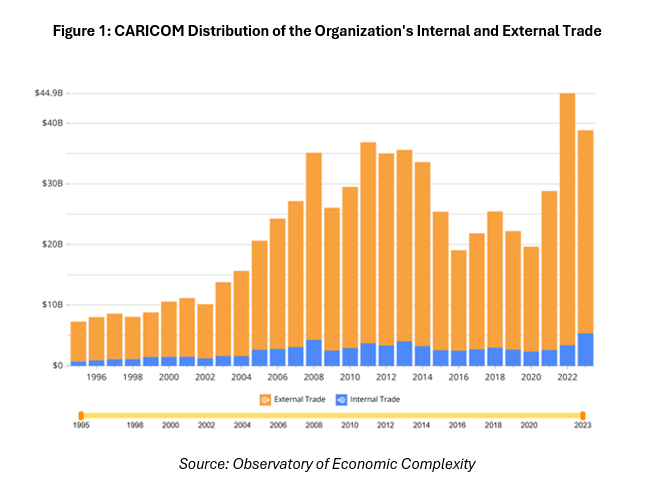

In a region bound by the blue expanse of the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean, where nations share centuries of intertwined history, the Caribbean’s greatest paradox is that the waters connecting it have also become a significant barrier. Despite notable strides in political and financial cooperation through CARICOM (Caribbean Community) and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), the physical movement of goods within the region remains fragmented, costly, and inefficient. According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC, 2023), only 13.9% of CARICOM’s total exports were traded within the regional bloc, while 86.1% were directed toward external markets. This imbalance highlights how weak transport infrastructure, high shipping costs, and underperforming ports have long suppressed intra-regional trade, leaving it stagnant for nearly two decades and among the lowest of any regional bloc globally. By contrast, intra-EU exports account for between 50 and 75% of total trade within the European Union, while the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) records intra-bloc trade of roughly 22 to 24%. These figures underscore a stark reality: the Caribbean’s integration challenge is not merely one of policy harmonisation but fundamentally one of connectivity. Until the region addresses its logistical fragmentation, the dream of a truly unified Caribbean market will remain an aspiration adrift at sea.

The Reality that Defies Geography

Shipping costs in the Caribbean are not merely a logistical inconvenience, they constitute a major economic handicap. According to the Association of Caribbean States (ACS), logistics costs in Latin America and the Caribbean account for between 16 and 26% of GDP, compared with approximately 9% in OECD economies. For many goods, these costs represent as much as 35% of product value and even higher for smaller enterprises, compared with 8% in OECD countries and around 10% in the United States. Delays in customs clearance across the region further increase transport costs by an additional 4 to 12%.

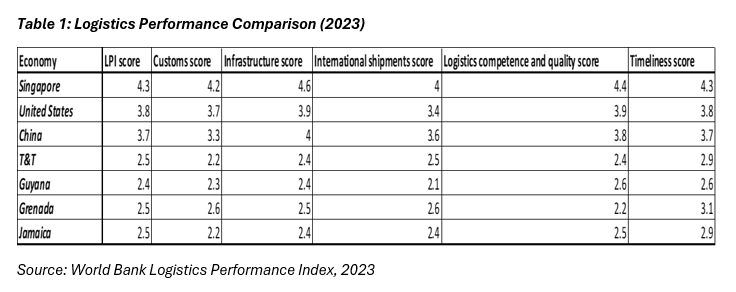

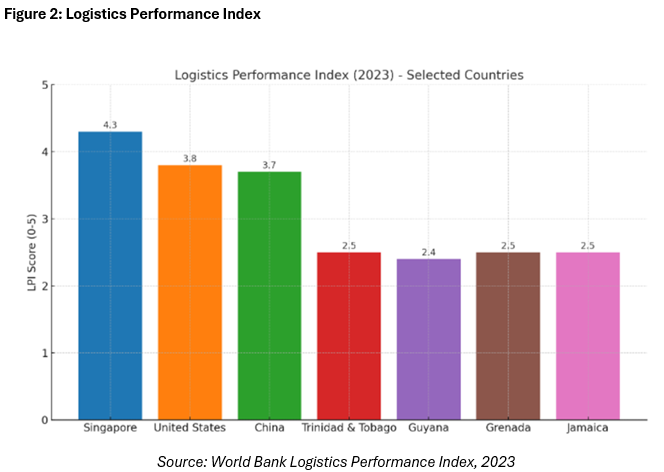

The World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index consistently ranks Caribbean economies well below European Union standards in measures such as shipping efficiency, infrastructure quality, and customs performance. In the 2023 LPI, most Caribbean states scored between 2.3 and 2.7, while EU countries averaged above 3.5 on a five-point scale, indicating smoother, faster, and cheaper trade flows across Europe.

These disparities make regional trade significantly more expensive than in other integrated markets. In the European Union, for instance, the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) links over 100,000 kilometres of roads, railways, and ports, harmonizing infrastructure and standards to lower shipping times and costs. By contrast, the Caribbean’s logistics ecosystem remains fragmented, characterized by small shipment volumes, limited inter-island routes, and inconsistent customs procedures. The consequences extend beyond freight: high logistics costs feed directly into higher consumer prices, weaker export competitiveness, and reduced productivity. For many small and medium-sized enterprises, the cost of moving goods within the region can erase narrow margins, making production less viable. As a result, the Caribbean remains economically disconnected despite its proximity and shared waters.

Impact on Private Sector Competitiveness and Diversification

Beyond macroeconomic costs, weak logistics undermine the competitiveness of Caribbean businesses and limit prospects for economic diversification. High intra-regional shipping costs, small shipment volumes, and fragmented port services raise operational expenses, reduce profit margins, and constrain firms’ ability to scale. For small and medium-sized enterprises, these inefficiencies can determine survival.

Manufacturers and agro-processors often face paradoxical situations: exporting to a neighbouring island may cost more than shipping the same goods to foreign countries. Agricultural producers across the Windward Islands encounter spoilage due to infrequent shipping and limited refrigerated cargo. Light manufacturing and craft industries struggle to access regional markets because fragmented customs procedures, inconsistent documentation, and irregular shipping schedules delay deliveries and inflate costs.

The cumulative effect is persistent reliance on external markets. Intra-regional trade has remained low within CARICOM trade, constraining the development of regional value chains and limiting diversification beyond traditional sectors such as energy, tourism, and primary commodities. Without strategic interventions to reduce logistics costs and streamline transport, Caribbean firms will continue to face structural disadvantages compared with competitors in more integrated regions like the EU or ASEAN.

Enhancing Caribbean Logistics: An EU Framework

Despite persistent logistical challenges, the path to regional trade efficiency lies in targeted investments and coordinated policy reform. Strengthening port infrastructure, expanding maritime connectivity, and embracing digital customs systems could transform bottlenecks into drivers of economic integration. Lessons from the European Union demonstrate that harmonized infrastructure planning and regulatory alignment are essential to improving trade efficiency and fostering competitiveness.

Investment in Infrastructure and Technology

Modernizing Caribbean ports and logistics systems requires an integrated regional approach. The European Union’s Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) provides a relevant model for coordinated infrastructure investment. TEN-T integrates multiple transport modes, roads, railways, inland waterways, ports, and airports, to create seamless connections between regions and facilitate the free movement of goods and people across member states.

TEN-T specifically aims to address missing links, bottlenecks, and gaps within the transport system while ensuring interoperability and environmental sustainability. The network is structured into three levels, core, extended core, and comprehensive, with completion targets set for 2030, 2040, and 2050. It includes nine European Transport Corridors that serve as the main arteries of intra-EU trade and investment. Corridor governance structures enable coordination among countries and stakeholders, ensuring timely implementation of cross-border projects.

For the Caribbean, adopting a similar, regionally coordinated logistics framework could yield long-term economic benefits. Establishing strategic maritime hubs and modern logistics facilities would improve efficiency, reduce dependence on extra-regional transhipment routes, and enhance trade competitiveness, particularly for time-sensitive and high-value exports.

Standardization and Process Optimization

The success of TEN-T also stems from harmonized technical and operational standards. According to the European Parliament’s analysis of the TEN-T Regulation, uniform requirements for infrastructure, customs procedures, and safety protocols reduce administrative barriers and facilitate cross-border operations. Applying similar harmonization within the Caribbean, including standardized documentation, customs inspections, and digital data systems, could reduce transaction costs and create greater predictability for traders.

Leveraging Public-Private Partnerships

Public-private collaboration has been central to Europe’s infrastructure modernization strategy. Under TEN-T, many projects are co-financed through partnerships involving the EU, national governments, and private sector actors, supported by instruments such as the Connecting Europe Facility and the European Investment Bank. This blended financing model has enabled Europe to advance complex projects in a financially sustainable manner.

The Caribbean could replicate this approach by encouraging public-private partnerships in areas such as port modernization, cold-chain logistics, and digital trade systems. For private businesses, this could mean improved access to modern facilities, faster cargo handling, and reduced operational costs. Governments could benefit from leveraging private capital to develop critical infrastructure while minimizing fiscal risk. Such partnerships would also foster innovation, technology transfer, and workforce development, ultimately increasing regional capacity and competitiveness.

Benefits of a Modernized Logistics Ecosystem

TEN-T has improved multimodal connectivity and addressed key transport bottlenecks in Europe, although large-scale projects often encounter cost overruns and delays. Overall, it has enhanced infrastructure planning, operational efficiency, and supply chain resilience, while integrating peripheral regions into the single market.

For the Caribbean, adopting a coordinated transport planning and investment model could yield substantial economic benefits. Harmonizing logistics and regulatory frameworks across CARICOM and OECS member states would facilitate smoother movement of goods, reduce administrative delays, and lower transaction costs. Strategically located regional hubs could serve as nodes in an integrated supply chain, ensuring that perishable, high-value, and time-sensitive goods are transported efficiently within the region and to external markets.

Investments in integrated infrastructure, standardized operational procedures, and digital logistics platforms would allow the Caribbean to overcome fragmented networks and achieve a more cohesive, reliable, and resilient trade system. Such improvements could enhance participation in global value chains, attract private investment, and stimulate economic diversification beyond traditional sectors. Over time, a coordinated regional logistics framework could transform geography from a structural limitation into a competitive advantage, supporting sustainable growth, job creation, and high-value trade corridors across the Caribbean.

Key Considerations and Challenges

Implementing advanced logistics frameworks in the Caribbean requires careful planning. Infrastructure upgrades must be supported by concessional financing and risk-sharing mechanisms to manage fiscal constraints. Regulatory harmonization must balance national sovereignty with interoperability and efficiency. Capacity building is essential to operate advanced logistics systems and ensure long-term maintenance. Environmental sustainability should also guide development, including green port initiatives and low-carbon technologies. Drawing lessons from the EU’s TEN-T experience, Caribbean nations can emphasize coordination, efficiency, and sustainability to build a modern logistics ecosystem that strengthens regional integration, competitiveness, and economic resilience.

Conclusion: Turning the Caribbean’s Waters from Barrier to Bridge

The Caribbean’s paradox is clear: surrounded by water that could unite its economies, the region remains fragmented and economically disconnected. Weak logistics, high shipping costs, and inefficient ports have kept intra-regional trade stagnant, curtailed private sector growth, and limited economic diversification. The path forward is tangible. Investment in regional logistics hubs, harmonization of customs processes, reliable inter-island shipping routes, and digital trade facilitation can turn these waters from barriers into bridges. Lessons from the EU and other integrated regions demonstrate that coordinated infrastructure and regulatory frameworks can dramatically lower costs, increase trade flows, and strengthen private sector competitiveness. For CARICOM and OECS nations, the opportunity is clear: by prioritizing logistics reform and strategic investment, the Caribbean can create a truly connected market, where businesses trade efficiently, value chains span islands rather than continents, and the region’s shared geography becomes an economic strength rather than a constraint.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment, or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.