Momentum in Motion

Commentary

When Finance Minister Davendranath Tancoo rose to deliver Trinidad and Tobago’s (T&T’s) 2026 National Budget, T&T First: Building Economic Fairness through Accountable Fiscal Policies, energy featured prominently. Though the address covered several priorities, from social equity to fiscal prudence, the emphasis on revitalizing the energy sector highlighted its continued centrality to the nation’s growth strategy. Against a backdrop of sluggish expansion, rising fiscal pressures, and shifting global commodity dynamics, the budget outlined a vision of economic recovery tied to hydrocarbons, aimed at restoring momentum and rebuilding confidence.

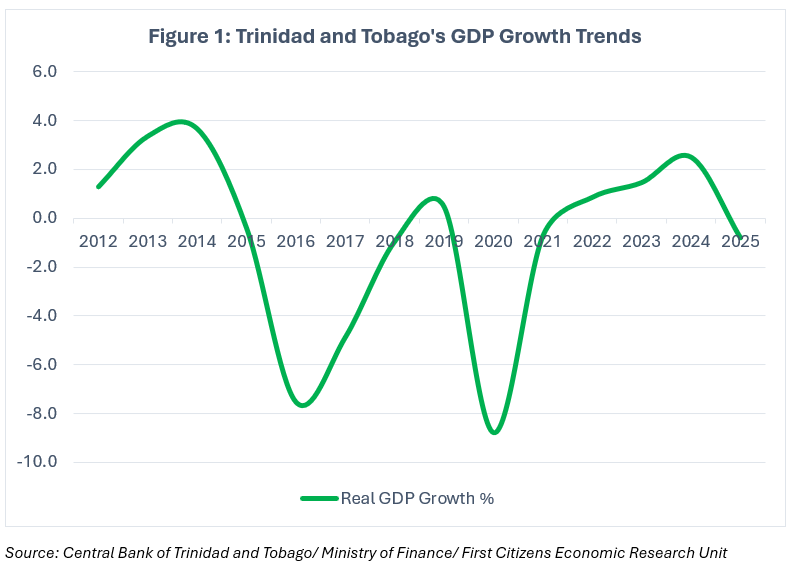

For over a decade, T&T’s economic performance has closely mirrored trends in energy production. Real GDP growth in 2024 stood at 2.5%, according to the Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago (CBTT). Yet, over the past decade, the economy has lost considerable ground, with real GDP falling from TTD187bn in 2014 to TTD154.9bn in 2024, a contraction of about 17%. The 2024 performance reflected a cautious rebound from the difficult years between 2015 and 2021, shaped by energy price declines and the COVID-19 shock. Still, the Ministry of Finance’s Review of the Economy 2025 points to lingering weakness, projecting a 0.8% contraction following three years of modest recovery.

For a country long described as the Caribbean’s energy capital, this budget was both familiar and forward-looking. Familiar, because oil and gas remain its fiscal anchor, and forward-looking, because the policy agenda places renewed focus on domestic production, downstream efficiency, and investment in emerging areas such as renewable energy and industrial innovation. The coming years will test whether this renewed energy focus can translate into broader, more sustainable growth for the national economy.

Recovering Momentum?

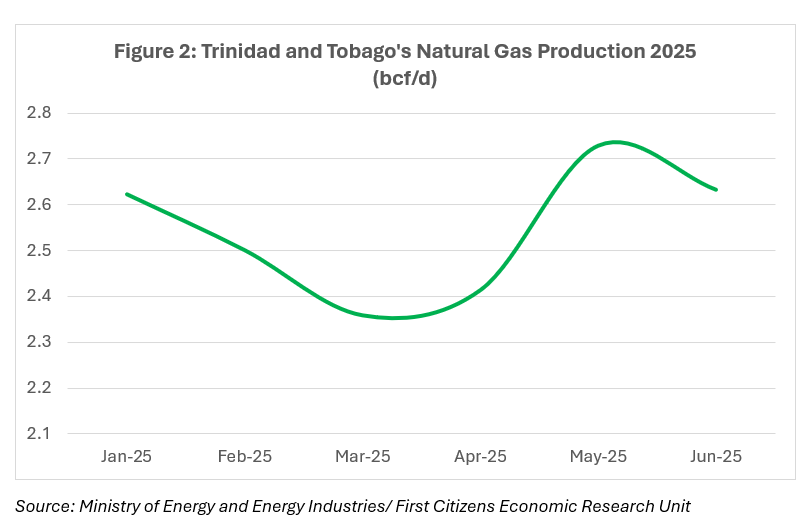

At the heart of T&T’s economy, lies the energy sector, its greatest strength and most enduring vulnerability. The National Budget indicates the government is counting on a steady recovery in the sector to anchor growth and fiscal revenue over the medium term. After years of subdued output, projections now point to a measured rebound. Natural gas production, which averaged about 2.6 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) in early 2025 (Figure 2), is expected to rise to roughly 3.2 bcf/d by 2027, supported by new upstream activity and the commissioning of major projects. The Manatee field, estimated to hold more than 2 trillion cubic feet of gas, is poised to play a pivotal role in expanding supply to LNG and petrochemical plants once operations commence in 2027.

According to the most recent data from the Ministry of Energy and Energy Industries (MEEI), average natural gas production in the first half of 2025 stood at roughly 2.54 bcf/d, with output fluctuating between 2.36 bcf/d in March and 2.73 bcf/d in May before settling near 2.6 bcf/d as of June 2025. The gradual pace of recovery highlights the lingering constraints on field output and the sector’s dependence on a few major producers, chiefly BPTT, Shell, and EOG Resources.

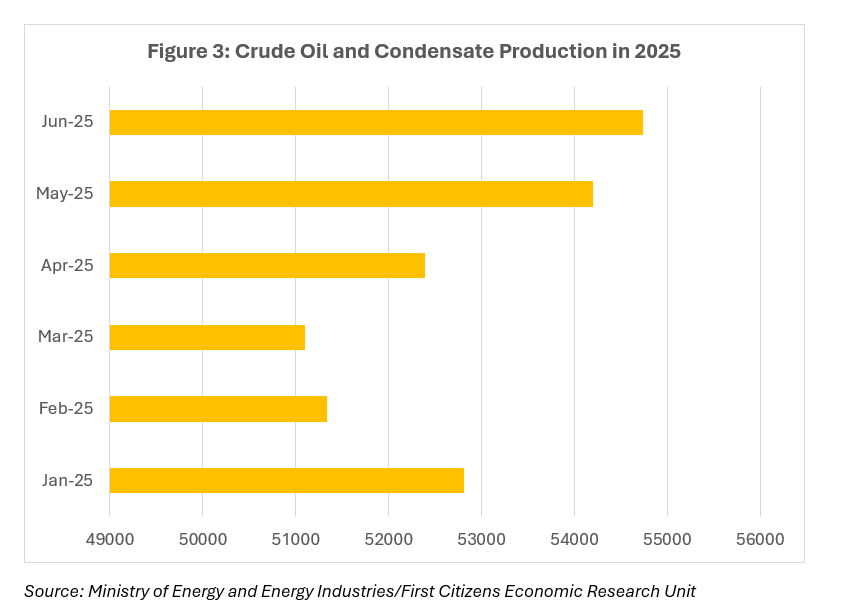

On the oil side, production has shown early signs of recovery. According to the Budget, crude oil and condensate output averaged 52,357 barrels per day in April 2025 (Figure 3), rising to 55,257 barrels per day by August, an increase of nearly 3,000 barrels. Gains were led by bpTT, EOG Resources, and Heritage Petroleum, supported by the Mento Development Project, which achieved first production in May. Heritage has since expanded its drilling campaign, while Perenco’s acquisition of shallow-water assets from bpTT and Woodside is expected to further lift mature-field output in the coming quarters.

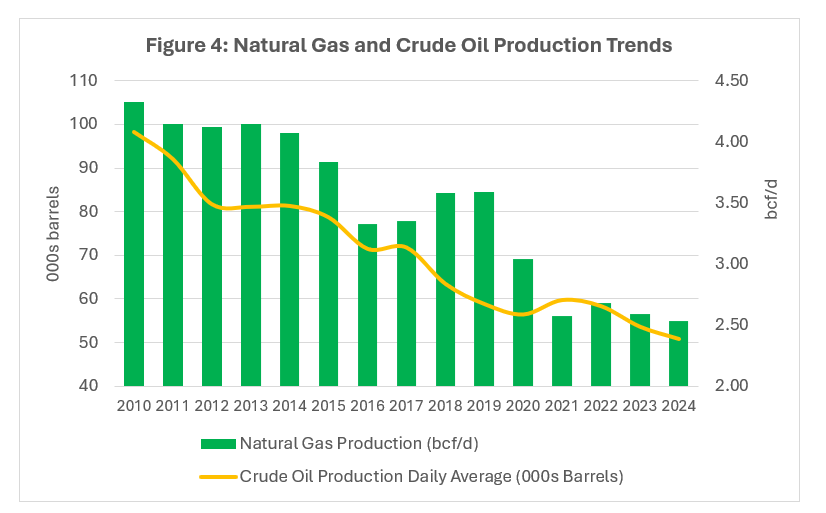

Overall, oil production has stabilized at around 52,800 barrels per day on average in 2025 (Figure 3), marking a cautious but welcome shift after years of decline. While this improvement signals gradual recovery, it remains well below historical levels, as oil output has fallen by nearly two-thirds since 2005, when production averaged 144,000 barrels per day, while natural gas production has halved since its 2009 peak of 4.5 bcf/d (Figure 4).

Using reference prices of USD73.25 per barrel for oil (down from USD77.80 in 2025) and USD4.25 per MMBtu for gas (up from USD3.59 in 2025), total government revenue is projected at TTD55.4bn against expenditure of TTD59.2bn resulting in a deficit of TTD3.9bn, or 2.2% of GDP.

Still, the budget’s success depends not only on upstream recovery but also on the strength of the supporting ecosystem. The Energy Chamber notes that the energy services subsector alone contributes around TTD1.5bn to GDP annually and sustains thousands of skilled jobs, particularly in South Trinidad and surrounding industrial communities. Any meaningful recovery in gas output therefore carries wider benefits for employment, local enterprise, and fiscal performance. Yet history shows that higher production alone is not enough. Without consistent investment, institutional reform, and timely project execution, today’s rebound could easily slip into another cycle of lost potential.

Macro-Economic Linkages and Fiscal Stakes…

The fiscal interdependence between T&T’s energy sector and the broader economy remains deeply entrenched. The Heritage and Stabilisation Fund (HSF) continues to act as a vital buffer against commodity price volatility, though its sustainability is ultimately tied to upstream performance. As energy receipts fluctuate, so too does the government’s fiscal space.

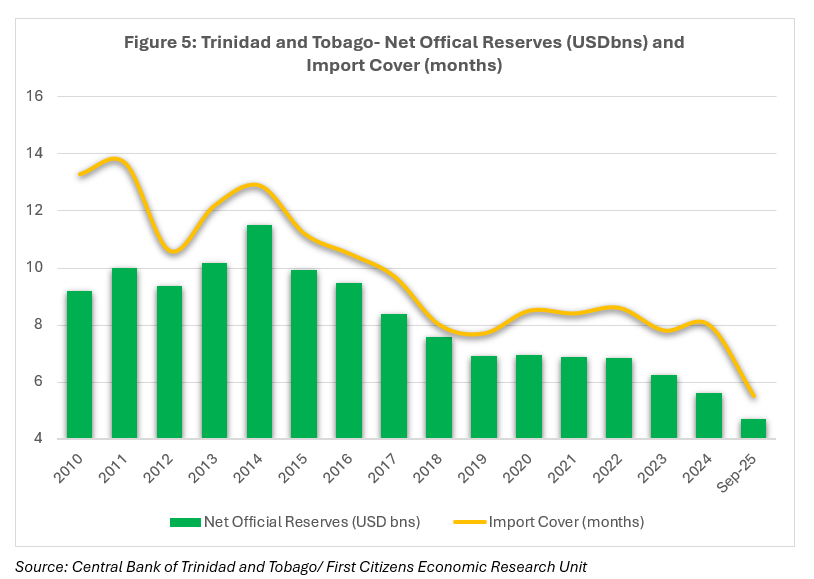

According to the Budget Address, T&T’s Net Official Reserves have declined significantly over the past decade, falling from USD11.5bn at the end of 2014, equivalent to 12.9 months of import cover to USD5.6bn at the end of 2024 (Figure 5), equivalent to 8 months of import cover. CBTT data exhibit a continued downward trend, with reserves slipping further to USD4.7bn at the end of September 2025, representing 5.5 months of import cover, compared to USD5.7bn and 8 months of import cover during the same period in 2024. This sustained decline highlights how years of weak energy production and lower export receipts have gradually eroded external buffers, heightening vulnerability to external shocks and tightening foreign exchange conditions.

A sustained production rebound could therefore deliver more than higher output; it could rebuild reserves, ease foreign exchange pressures and help stabilize inflation expectations.

However, the path to resilience remains narrow. While the non-energy sector has shown areas of strength, particularly in manufacturing (food, beverages, and tobacco expanded by 17.1% in 2024) and transport and storage (5.6%), these gains are from a small base and have yet to meaningfully offset energy-sector dependence.

Without concurrent diversification and productivity growth, an energy-led recovery risks reproducing the volatility it seeks to escape, one where fiscal stability, external buffers, and inflation control rise and fall with the price of a barrel.

Turning Energy Potential into Economic Design…

T&T cannot build lasting stability on hydrocarbons alone – discipline and design are critical for the sustainability of the economy. The current potential rebound, though welcomed, must be used as a bridge toward a broader transformation rather than a ‘comfort zone’ that delays reform.

First, fiscal management should focus on strengthening the Heritage and Stabilisation Fund (HSF) so that it operates as a more reliable shock absorber. Although the Fund already follows a rule-based system, requiring deposits when energy revenues exceed budget and allowing withdrawals when they fall short, its application has been inconsistent over the years, particularly during 2020-2021 when amendments to the Act under Section 15A allowed exceptional withdrawals to cushion pandemic-related fiscal pressures. Ensuring strict adherence to these rules, updating the reference price mechanism to reflect current market realities, and improving public reporting on inflows and withdrawals would enhance transparency and fiscal credibility. A stronger, more disciplined HSF framework would allow T&T to save more during commodity upturns and draw down responsibly during downturns, reducing the economy’s exposure to volatile energy prices. The IMF’s 2024 Article IV consultation similarly encouraged strengthening fiscal anchors by adopting a sovereign asset-liability management framework and a formal fiscal rule that integrates HSF operations into the medium-term fiscal framework, reforms that are already underway with technical assistance from the Fund’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department.

Secondly, diversification needs to move from narrative to measurable outcomes. Targeted incentives for export-oriented manufacturing, renewable energy and the digital economy could gradually reduce dependence on energy-linked revenues. T&T’s comparative advantage in industrial services and logistics could also be leveraged to support regional value chains emerging in Guyana and Suriname.

Third, competitiveness must become central to the investment agenda. While ExxonMobil’s return signals renewed confidence in upstream prospects, according to the Budget address, broader investor sentiment will depend on the speed and predictability of project execution. Streamlining permit approvals, modernizing port and customs systems, and improving transparency in state-enterprise operations could strengthen the overall business climate.

Finally, resilience should be treated as a macroeconomic policy goal. The past decade has shown that economic shocks, whether from pandemics, hurricanes, or commodity swings, quickly spill over into fiscal and external accounts. Building resilience means diversifying revenue sources, training the labour force to adapt to changing industries, and embedding climate adaptation in infrastructure planning.

The coming years will test whether Trinidad and Tobago can convert this window of opportunity into structural change. Geography cannot be altered, but economic design can.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.