Is India the New China? The Global Factory Shift

Commentary

For over two decades, China has dominated global manufacturing, earning its title as the “world’s factory.” This rise began in the late 1970s, when sweeping economic reforms shifted the country away from rigid central planning toward a more market-oriented system. Central to this transformation was the introduction of Special Economic Zones (SEZs), which played a critical role in attracting substantial foreign direct investment and driving export-led industrial growth. China’s manufacturing success was propelled by a strategic combination of low labour costs, robust infrastructure, favourable policy frameworks, and deep integration into global trade networks. As a result, the country emerged as a key supplier of a vast array of goods, from electronics and textiles to machinery and consumer products, firmly establishing its place at the centre of global supply chains.

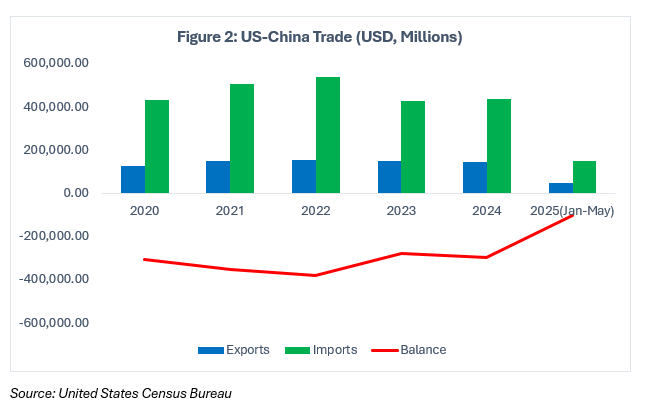

More recently however, the global economic landscape has been shifting. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the vulnerabilities of over-dependence on a single country for critical production. China’s strict lockdowns and port disruptions triggered widespread supply shortages, leading multinational companies to reassess the resilience of their sourcing strategies. Simultaneously, intensifying geopolitical tensions, particularly the ongoing trade and technology conflict between the United States (US) and China, have added a layer of strategic risk. Rising wages and regulatory uncertainties within China have further eroded the cost advantages that once made it so attractive to foreign manufacturers.

Amid this backdrop, global firms are increasingly exploring alternatives, a move driven not by a desire to exit China completely, but to diversify their operations and build supply chain resilience. Among the contenders, India has emerged as a compelling choice, offering a potent mix of demographic strength, policy reforms, and growing digital capabilities. The question is no longer whether China will be supplemented but whether India can truly rise to become the new manufacturing powerhouse of the world.

India: A Rising Contender

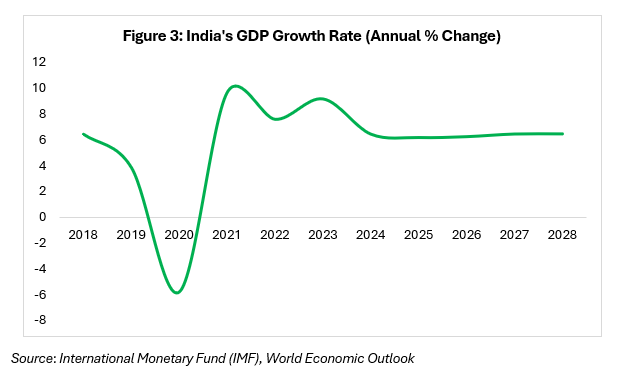

India’s economic transformation has been both robust and dynamic, marked by a strong post-pandemic recovery. As one of the fastest-growing economies globally, India’s real GDP is projected by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to rise from a contraction of 5.8% in 2020 to 6.2% by 2025. A key contributor to this growth has been the rapid expansion of the export sector, which continues to gain global competitiveness. India’s emerging role in global manufacturing is not merely a by-product of shifting geopolitical currents, it is underpinned by fundamental structural strengths. These include a large and youthful workforce, policy reforms, digital infrastructure, and targeted government initiatives aimed at boosting domestic production.

According to the United Nations’ World Population Prospects (WPP), India has a significant demographic advantage over China, with a median age of 28.2 years compared to China’s 39 years, a ten-year gap that highlights India’s youthful population. India is also now the world’s most populous nation, with its population projected to exceed 1.4 billion by the end of 2025. This demographic profile offers a substantial labour force advantage at a time when China’s population is aging, and its working-age population is in decline. In addition, India’s expanding middle class, expected to approach 600 million by 2030, is driving robust domestic consumption and establishing a strong foundation for sustained, demand-led economic growth.

In recent years, India has taken bold steps to strengthen its manufacturing base and attract global investment. Central to this effort are a series of reforms introduced across three main areas: production-linked incentives (PLIs), tariffs, and domestic content requirements (DCRs). Measures such as the “Make in India” initiative, launched in 2014 was strategically utilized to position the country as a global hub for design and manufacturing. Another standout component is the PLI Scheme, introduced in 2020, which provides financial incentives to companies that increase production in key sectors such as electronics, pharmaceuticals, automobiles, semiconductors, and renewable energy. Global giants like Apple and Samsung have already benefited from the programme, enhancing their competitiveness and expanding their operations. As a result, India has experienced a surge in foreign direct investment (FDI) from companies seeking to reduce their reliance on China.

In addition to its manufacturing and industrial policy reforms, India has made significant progress in strengthening its digital landscape. These efforts reflect a deliberate and sustained strategy to build a robust digital backbone capable of supporting the country’s broader economic ambitions. With over 800 million internet users, India is now one of the most connected nations worldwide. The success of its digital public infrastructure, particularly the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), has positioned India as a global leader in fintech and digital governance. This digital revolution is not limited to consumer finance and government services; it now permeates the manufacturing sector as well. Through the adoption of smart factories, automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and data-driven logistics, India is embracing Industry 4.0 to boost productivity, efficiency, and scalability across supply chains. These advancements are laying the groundwork for a more competitive and integrated industrial base. Moreover, India’s long-standing strengths in software development and IT services are beginning to converge with its ambitions in hardware manufacturing. Initiatives aimed at developing semiconductor capabilities, electronics manufacturing, and 5G infrastructure signal a shift toward a more diversified role in the global technology value chain. As a result, India is not only becoming a key player in digital innovation but also positioning itself as a future leader in end-to-end tech-driven industrial development.

China +1 Strategy: A Shift, not a Replacement:

By definition, the China+1 strategy involves companies diversifying their manufacturing footprint by adding at least one additional country to reduce dependence on China. As global conditions remain highly volatile, firms are increasingly adopting this approach for several reasons: risk mitigation, cost management, supply chain resilience, and expanded market access. India has become a major beneficiary of this shift.

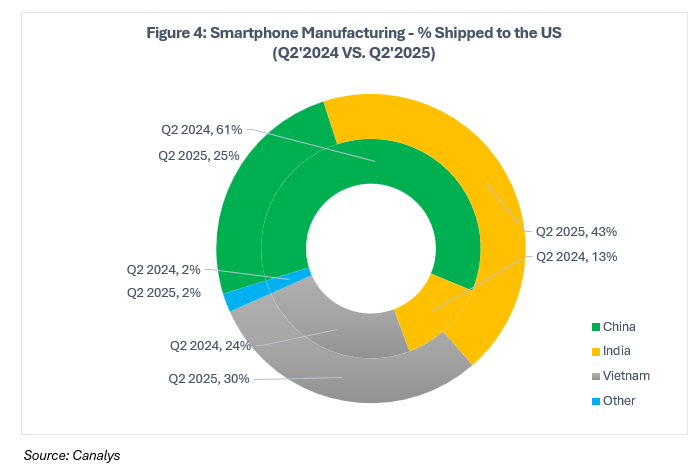

The transition is already becoming evident. According to the most recent data, Apple intends to manufacture the majority of its iPhones sold in the US at Indian facilities by the end of 2026. While production costs in India are estimated to be 5–8% higher than it would in China, the overall strategy remains economically viable. This is largely due to India’s lower import duties, which is estimated to be approximately 25% in comparison to the 30% in combined tariffs that was threated on imports from China.

Samsung has also ramped up its investment in India, building one of its largest mobile phone manufacturing plants near New Delhi. At the same time, Indian electronics firms such as Dixon Technologies are expanding rapidly to meet rising global demand. The pharmaceutical sector is also seeing increased activity, with India continuing to dominate global generics manufacturing. Similarly, fashion retailers like Zara and H&M are actively diversifying their sourcing strategies, shifting more apparel and textile production from China to India.

Challenges Ahead: India’s Bottlenecks

While the momentum is on India’s side, the road ahead is far from smooth. One of the most pressing challenges is infrastructure. Despite notable progress, many regions in India still suffer from inadequate transport networks, erratic electricity supply, congested ports, and high logistics costs. These issues reduce efficiency and add to the cost of doing business.

Another persistent issue is bureaucracy and regulatory complexity. Although reforms have improved the business climate, companies still face delays in environmental clearances, frequent policy changes, and complex tax compliance procedures. Land acquisition, in particular, is a contentious and time-consuming process, often stalling large-scale industrial projects.

Lastly, the federal nature of India’s governance means that investment climates can vary widely by state. A company operating in Tamil Nadu may face very different labour laws and infrastructure support compared to one in Uttar Pradesh. Achieving national consistency in policy implementation remains a critical hurdle.

Conclusion: The Path to Becoming “The Next China”

India is not yet the new China, but it is undeniably emerging as a critical pillar in the global manufacturing landscape. The shift is real, but gradual. Rather than a wholesale replacement, the transformation will be sector-specific, strategic, and dependent on the ability to maintain momentum through reforms and investments. For India to fulfil its potential, it must double down on infrastructure development, human capital investment, and regulatory predictability. With sustained policy focus and execution, India could not only share the stage with China but also define a new model for resilient, diversified, and inclusive global manufacturing in the 21st century.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.