Feeding the Nation or Funding the Idea?

Commentary

Introduction:

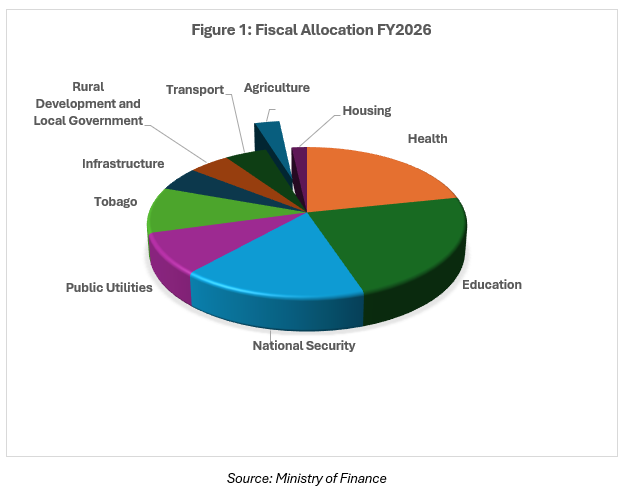

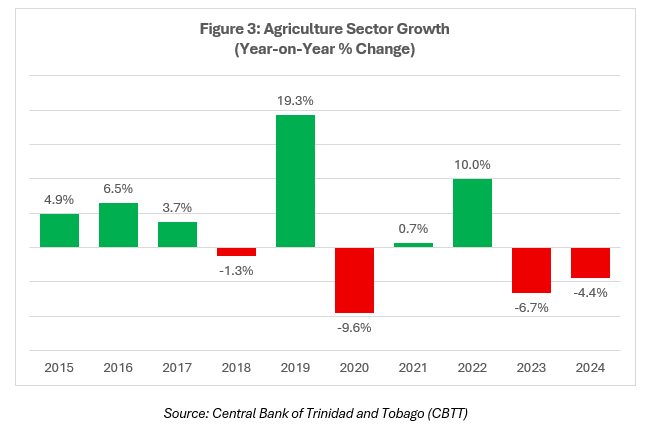

Trinidad and Tobago’s agricultural sector is at a critical crossroads. The 2025-2026 national budget has allocated TTD1.13 billion to the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries, an amount that signals the government’s intent to strengthen food security, boost rural employment, and reduce reliance on imports. For decades, agriculture has been contributing less than 1% to national GDP despite the country’s fertile land, favourable climate, and historical legacy of food production. The sector has struggled to compete alongside the energy and services industries, which dominate both government revenues and employment. As a result, agricultural output has declined, rural populations have aged, and domestic food production has failed to keep pace with consumption.

A Decade of Rising Food Imports and Economic Implications

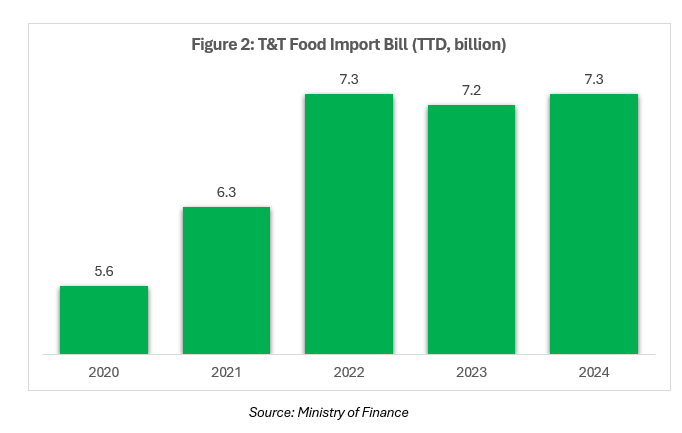

Over the past decade, Trinidad and Tobago’s dependence on imported food has grown steadily, an alarming trend for a country that once prided itself on self-sufficiency in key staples like rice, poultry, and vegetables. The national food import bill, which totalled around TTD56.9 billion between 2003 and 2016, averaging around TTD3.85 billion annually, surged to approximately TTD7.3 billion in fiscal 2024. This escalation is not merely a reflection of population growth or changing consumption patterns, it is a symptom of deep-rooted structural weaknesses in local production capacity, agricultural competitiveness, and policy continuity.

The underlying issue is that while consumption has grown, domestic agricultural output has largely stagnated. Farmers face persistent challenges, ranging from limited access to credit and mechanization to fragmented distribution systems and outdated extension services. Land availability, though abundant in theory, is often constrained by bureaucratic inefficiencies in lease approvals and inconsistent land-use planning. The result is a widening gap between what the nation consumes and what it produces, forcing the country to rely heavily on imports to fill that gap.

The economic implications are profound and far-reaching. Heavy reliance on imported food exposes Trinidad and Tobago to global price volatility, foreign exchange pressures, and supply chain disruptions. When global food prices spike, due to conflicts, droughts, or shipping bottlenecks, those costs are directly transmitted into local inflation. For instance, during the 2022 global commodity surge, local food inflation peaked, disproportionately affecting lower-income households. This inflationary pass-through not only erodes purchasing power but also exacerbates inequality, as poorer households spend a larger share of their income on food.

Moreover, the persistent outflow of foreign exchange to pay for food imports undermines the country’s external balance and economic resilience. Trinidad and Tobago earns most of its foreign exchange from energy exports, but as energy production and prices fluctuate, so too does the availability of foreign currency. Every dollar spent on imported food is a dollar not invested in domestic value creation, whether in manufacturing, renewable energy, or technological innovation. In essence, the rising food import bill represents a quiet leakage of national wealth and an opportunity cost that weakens long-term development prospects.

This structural dependence also carries strategic risks. Events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and global shipping disruptions revealed how vulnerable food-importing nations are when supply chains tighten. Trinidad and Tobago, with its high import dependency, found itself exposed to both availability and price shocks. Strengthening local agriculture is therefore not just about supporting farmers or rural communities, it is about enhancing national security, economic sovereignty, and resilience in an increasingly uncertain global environment.

Decades of Agricultural Underperformance

Persistent challenges have limited growth and productivity in the agriculture sector over the years. Access to land remains a major barrier, with many smallholders and prospective farmers waiting for formal leases. Without secure land tenure, farmers often struggle to invest in infrastructure, mechanization, or long-term crop planning, which restricts the expansion of productive farmland.

Access to finance is another critical constraint. Many farmers have difficulty obtaining loans or credit for equipment, inputs, or expansion. Limited lending capacity, coupled with the absence of risk-sharing mechanisms or crop insurance, makes it difficult for farmers to invest confidently, particularly in high-value or innovative agricultural practices.

Technology and productivity gaps continue to affect farm operations. Many farms rely on traditional methods, with limited mechanization, greenhouse adoption, or modern digital tools. This results in lower yields, higher post-harvest losses, and slower adoption of efficiency-enhancing practices. Small and medium-sized farmers often face challenges in accessing both modern equipment and the necessary training to use it effectively.

Climate vulnerability also poses significant risks. Droughts, floods, soil erosion, and other extreme weather events can disrupt production cycles and reduce yields. Investments in irrigation, water management, and climate-resilient farming practices are often insufficient or inconsistently implemented, leaving farmers exposed to environmental shocks.

Supply chain and market access issues further constrain growth. Farmers frequently encounter inconsistent pricing, limited transportation infrastructure, and inadequate storage and processing facilities. These factors make it difficult to sell produce efficiently or reach broader markets, reducing income stability and the ability to scale operations.

Finally, coordination and support across agricultural services can be fragmented. Farmers often face overlapping or unclear channels for technical assistance, training, and market facilitation. Improved coordination of extension services, supply chains, and support programs would help farmers access resources more efficiently and strengthen overall sector productivity.

Policies and Programmes in the 2025-2026 Budget

Fiscal and Tax Incentives: Lowering Costs, Raising Competitiveness

The 2025-2026 National Budget presents a structured agricultural policy, combining fiscal relief, infrastructure investment, targeted commodity programmes, and a clear focus on technology. Key fiscal measures include the removal of VAT on all machinery and equipment explicitly intended for agricultural use, as well as exemptions for components used in hydroponic and greenhouse farming. The Government also proposes to review and expand the zero-rating of items under Schedule 2 of the VAT Act to include fertilisers, plant-protection products, and veterinary medicines. Additionally, customs duty will be removed from animal feed used in poultry, cattle, and pig production.

These tax measures aim to reduce input costs, modernize production systems, and improve cost competitiveness across the food value chain, particularly in import-intensive sectors such as poultry and livestock. Such policies may improve price elasticity of domestic supply, encourage investment in capital-intensive technologies, and reduce reliance on foreign feed and fertiliser imports.

Targeted Commodity Strategy: Focus for Faster Productivity Gains

To address production inefficiencies, the Budget introduces a Three-Year Priority Commodities Programme, focusing on 15 high-demand products with annual emphasis on three crops and one livestock category. Key commodities include fine-flavour cocoa, Moruga pepper, aquaculture, and selected vegetables. By concentrating resources and extension services on a limited set of high-impact commodities, the Government aims to build comparative advantage and achieve measurable results within a defined timeframe. This approach aligns with regional best practices, particularly Guyana’s model of clustered investment in key crops and allows for better market development and performance tracking through clearer Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) frameworks.

Infrastructure and Land Development: Unlocking Private Investment

The Budget allocates TTD793.7 million for infrastructure and agri-tech projects, including irrigation networks, fisheries development, and land rehabilitation. Land-lease distributions from former estates such as Caroni and Orange Grove, alongside the development of residential-agricultural zones, are designed to promote tenure security and attract private investment. Improved irrigation and farm roads are not only logistical enablers, but they also reduce production risk, cut post-harvest losses, and stimulate the multiplier effects of private capital. From an economic perspective, these projects can raise the marginal productivity of land and labour, increase yield stability, and reduce the import bill through greater domestic output.

Climate Resilience and Smart Agriculture: Managing Risk through Innovation

The Budget reinforces climate resilience through incentives for greenhouses, water-harvesting systems, and a new crop-insurance framework. It also introduces support for Smart Agriculture and AI Farming, signalling a move toward precision-based practices and data-driven production. These measures enhance the sector’s ability to manage climate and price risks, enabling more predictable cash flows and improving creditworthiness among farmers. When paired with digitised farm data and insurance coverage, such measures can also expand access to formal financing, a key constraint historically noted in Central Bank agricultural surveys.

Youth and Human Capital: Building the Next Generation of Farmers

The Youth Agricultural Fund (YAF) and new education initiatives mark a shift toward long-term capacity building. Agriculture will be integrated into school curricula, and the YAF will finance agri-entrepreneurship, training, and incubation programmes. This dual approach of skills development and access to finance, seeks to rebuild the farmer pipeline and attract youth to agribusiness, helping to reverse an ageing demographic trend in rural areas. If successful, youth-led startups can boost innovation and link agricultural production to logistics, processing, and export services.

Export Development: From Niche Products to Global Markets

The Budget outlined the following targets as it relates to the agriculture sector: doubling agro-exports by 2028 and achieving TTD1 billion in agro-export value in the next fiscal year. Key products such as fine-flavour cocoa and Moruga pepper are identified as export growth drivers. Support through NAMDEVCO and other export-facilitating agencies, coupled with India’s donation of agro-processing equipment valued at USD1 million, reflects a clear value-added strategy. By focusing on high-value, differentiated exports, the policy aims to improve the country’s trade balance and foreign-exchange earnings, while fostering linkages between farming and manufacturing.

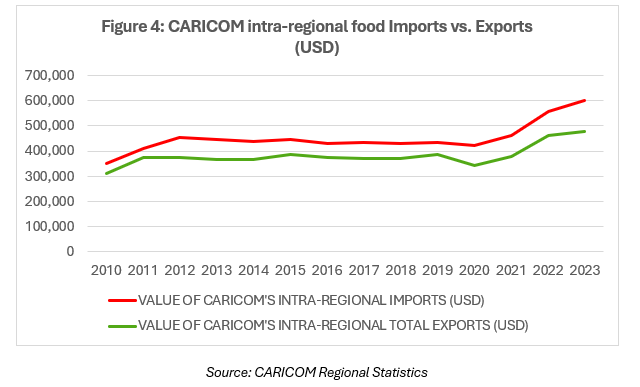

CARICOM’s “25 by 2025” Food Security Agenda

Trinidad and Tobago’s agricultural strategy, as outlined in the 2025-2026 Budget, seeks to position the country firmly within the broader regional framework of CARICOM’s “25 by 2025” initiative. This regional agenda aims to reduce the Caribbean’s food import bill by 25% by 2025, with the extended national ambition of achieving at least a 25% reduction by 2030.

By aligning with this initiative, Trinidad and Tobago acknowledges the dual objective of regional food security and export diversification. The alignment ensures that local policy measures, such as expanding domestic production of poultry, root crops, vegetables, and aquaculture, feed directly into CARICOM’s collective targets for reducing extra-regional imports. Simultaneously, it strengthens the foundation for scaling up agro-exports, particularly for niche, high-value commodities that can compete regionally and internationally.

In practical terms, this means increasing local self-sufficiency in key staples like poultry, pork, and selected vegetables, while enhancing agro-processing and packaging standards to meet CARICOM and international market requirements. Harmonising sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) standards, facilitating intra-regional trade logistics, and improving traceability systems will also be critical steps to ensure that Trinidad and Tobago’s agricultural output can circulate more freely across the single market.

In aligning national objectives with CARICOM’s “25 by 2025” targets, the 2025-2026 Budget underscores that agricultural transformation is not only about domestic food security but also about regional resilience and export competitiveness. The real test will be ensuring that production increases translate into measurable reductions in food imports, stronger participation in regional value chains, and a sustainable agro-export platform capable of driving growth beyond 2030.

Fiscal Priorities vs. Agricultural Productivity

Trinidad and Tobago’s 2025-2026 national budget maintains a relatively stable allocation to the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries, consistent with the levels of the previous two fiscal years. At face value, this continuity reflects policy steadiness and sustained recognition of agriculture’s role in economic diversification. However, a deeper economic assessment raises an important question: to what extent are these resources enhancing productive capacity, rather than sustaining administrative and short-term activities?

Over the years, a large share of agricultural expenditure has been recurrent rather than developmental. Recurrent spending, covering wages, maintenance, and subsidies, tends to dominate the budget, while capital investment in infrastructure, research, and technology adoption remains comparatively limited. This imbalance constrains the sector’s ability to generate long-term growth, as resources are primarily directed toward consumption rather than investment.

Implementation challenges also continue to weaken the effectiveness of public investment. Delays in procurement, project execution, and inter-agency coordination have often resulted in underutilization of funds, particularly for infrastructure and land development projects. From an economic standpoint, these delays reduce capital productivity, limiting the return on public investment and slowing the sector’s overall growth trajectory.

A further challenge lies in the weak link between expenditure and measurable performance outcomes. While budget documents outline allocations by department or initiative, they seldom include specific targets, such as increases in cultivated acreage, reductions in the food import bill, or gains in sectoral productivity. Without clearly defined and monitored performance indicators, it becomes difficult to assess the efficiency or impact of agricultural spending, thereby reducing fiscal accountability and data-driven policy evaluation.

Institutional fragmentation adds another layer of complexity. Several entities, including NAMDEVCO, the Agricultural Development Bank (ADB), the Land Settlement Agency, and various research institutions, operate within the agricultural ecosystem, often with overlapping functions and limited coordination. This dispersion of responsibility can dilute policy impact, as complementary initiatives such as land distribution, financing, and market access are not always integrated effectively.

From a macroeconomic perspective, improving the efficiency of agricultural spending has significant potential benefits. Trinidad and Tobago continues to spend billions annually on food imports, representing both a drain on foreign exchange reserves and a missed opportunity for domestic value creation. Redirecting even a modest portion of this outflow toward productivity-enhancing investments, such as irrigation, post-harvest processing, and agri-tech adoption, could yield meaningful returns through job creation, rural development, and reduced import dependency.

Conclusion: Breaking the Decade-Long Cycle of Underperformance

The 2025-2026 Budget captures many of the right intentions, fiscal incentives, youth engagement, technological investment, and infrastructure renewal. Over the past decades, Trinidad and Tobago’s agricultural output grew only marginally, while the food import bill climbed exponentially. To transform fiscal commitment into measurable progress, emphasis must be placed on execution, accelerating land tenure reform, linking finance to productivity outcomes, strengthening agricultural data systems, and holding agencies accountable for results. The lessons of the past years point clearly to one conclusion, without structural reform, each new budget risks becoming another well-intentioned but underperforming effort. If, however, the 2025-2026 agricultural agenda succeeds in bridging the gap between policy design and delivery, it could finally mark the beginning of a sustained shift toward food security, export diversification, and economic resilience.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment, or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.