Can We Reap Growth if We Keep Losing the Seeds?

Commentary

What happens when the best minds build someone else’s economy?

Imagine planting a tree that bears fruit once every generation. You water it, shield it from storms, and wait patiently for it to grow. But just as it begins to bear fruit, someone else picks it. That is the economic reality across the Caribbean: countries tend to invest heavily in cultivating talent yet reap diminishing returns as their most capable citizens emigrate before contributing meaningfully to the domestic economy. The result is not just a social loss, it is a macroeconomic constraint that leaks value from the region’s development path.

A Structural Drag on Development: The Macroeconomic Cost of Brain Drain in the Caribbean

What has long been labelled “brain drain” has evolved into a structural impediment to Caribbean development. The outflow of skilled professionals across the Caribbean is no longer just a by-product of globalization, it is a defining feature of underutilized labour markets, weakened institutional capacity, and suppressed productivity growth. Once viewed primarily as a demographic concern, it now constitutes a macroeconomic fault line constraining endogenous growth and amplifying fiscal inefficiencies. Despite consistent public investment in education and training, the returns on these expenditures increasingly accrue to foreign labour markets. Public institutions, particularly in health, education, and public administration, struggle to retain qualified professionals, resulting in widening capacity gaps. In turn, the region’s ability to build a robust domestic human capital base which is essential for innovation, service delivery, and inclusive growth, remains limited.

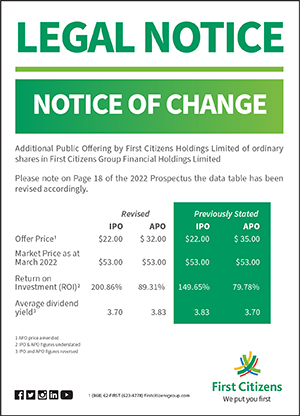

Tourism Analytics points to several structural factors exacerbating the issue: geographical isolation, limited economic diversification, vulnerability to climate change, and a chronic shortage of opportunities, especially for youths. These pressures collectively push the region’s most ambitious citizens to seek better prospects abroad. Between 2000 and 2022, an estimated 3.2 million people emigrated from the Caribbean, equivalent to about 7.3% of the region’s 2022 population, representing a significant demographic and economic loss. The Human Flight and Brain Drain Index from The Global Economy emphasizes the scale of this challenge. Guyana, for instance, registered a score of 7.9 out of 10 in 2024 (Figure 1), well above the global average of 4.98. While this marks a slight improvement from its 2016 peak of 9.4, the challenge persists: according to the US State Department, nearly 89% of university-educated Guyanese resided abroad in 2024.

Jamaica faces a similarly acute challenge. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates that over 80% of its tertiary-educated citizens, most trained locally now live abroad. Over the decades, more than one million Jamaicans have migrated, primarily to the US, United Kingdom, and Canada. The impact is significant: a net migration rate of two per 1,000 people was recorded in 2021, highlighting the steady erosion of the domestic skilled workforce.

The outcome is an enduring paradox: Caribbean countries cultivate skilled professionals who ultimately drive productivity gains in foreign economies, while domestic labour markets remain constrained and public sectors hollowed out. What then is the cost of lost potential? Beyond remittance inflows, the region forfeits the very productivity, innovation, and fiscal resilience that is needed to chart a sustainable development path.

Headline Growth, Workforce Strain…

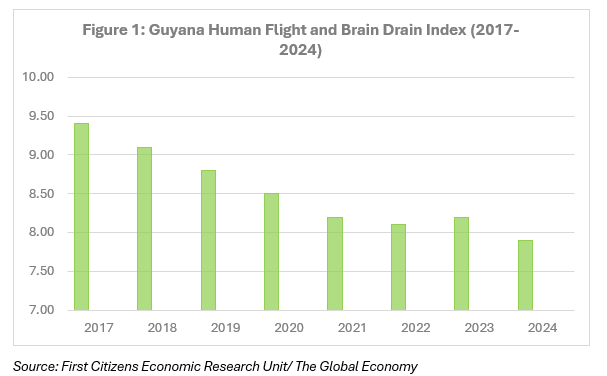

Guyana’s recent economic story presents a striking dichotomy: rapid macroeconomic expansion propelled by hydrocarbon wealth, colliding head-on with a persistent erosion of domestic human capital. Following a series of transformative offshore oil discoveries, Guyana has emerged as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), real GDP growth soared from 5.4% in 2019 to an estimated 43.6% in 2024, with a projected moderation to 10.3% in 2025 (Figure 2).

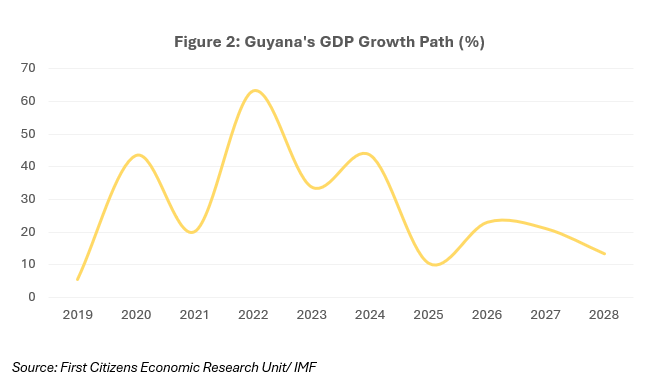

This extraordinary growth trend has been matched by strong improvements in the external sector. Once saddled with current account deficits as high as 24.8% of GDP in 2021, Guyana is now poised to record surpluses of roughly 24.6% by 2024 (Figure 3), fuelled largely by oil exports and robust public capital formation.

Yet, behind these headline figures lies a critical structural bottleneck: the depletion and underutilization of domestic human capital. Despite abundant growth opportunities, the labour market has been unable to respond. Foreign Secretary Robert Persaud estimates that over 100,000 positions remain vacant across critical sectors such as oil services, engineering, healthcare, construction, and public administration.

Labour market data from the International Labour Organization (ILO) reveals a challenging landscape in Guyana. As of the third quarter of 2021, the labour force participation rate was just 49.6%, notably lower than that of its regional peers. More concerning, long-term unemployment made up 38% of total joblessness, emphasizing deep-rooted structural obstacles to labour market entry. These issues are further compounded by high emigration levels, particularly among skilled workers, which continue to strain an already limited talent pool and hinder the labour market’s adaptability.

In response, the Government of Guyana has begun implementing measures to address these human capital constraints. Minister of Health Dr. Frank Anthony has pointed to a growing trend of diaspora return, driven by expanding economic prospects. At the policy level, the government has introduced its 2025–2035 National Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Policy, aimed at modernizing skills development, incorporating digital tools, and improving alignment with private sector demand. These efforts are reinforced by the Green State Development Strategy which outlines a broader agenda for economic diversification and sustainable workforce development.

Despite these policy efforts, implementation capacity remains an ongoing concern. The IMF notes that while public capital investment is projected to remain high at 12% of GDP in both 2023 and 2024, project execution continues to be constrained by a shortage of qualified professionals. The 2024 Mid-Year Budget Review explicitly acknowledges the risk of labour market mismatches and indicates that sector-specific manpower studies are underway to inform training and workforce alignment strategies. While these initiatives are encouraging, they remain largely reactive and are challenged by the country’s structurally limited skills base.

The ‘Growthless Jobs’ Phenomenon…

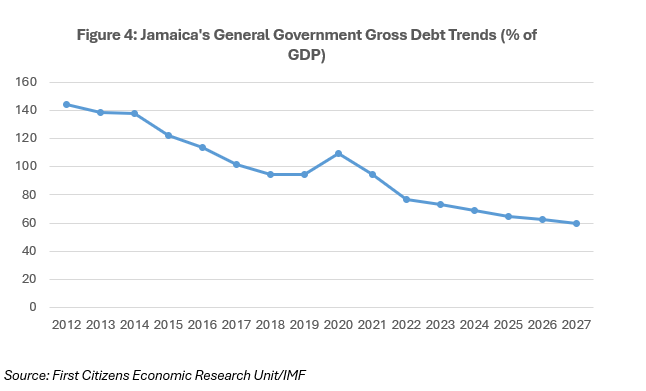

Jamaica presents a contrasting, yet equally instructive example of the Caribbean’s struggle with human capital attrition. Over the past decade, the country has achieved notable macro-fiscal consolidation. According to the IMF, Jamaica’s public debt declined from a peak of 144% of GDP in 2012 to 69.2% in 2024, with projections suggesting a further drop to 64.6% in 2025 (Figure 4).

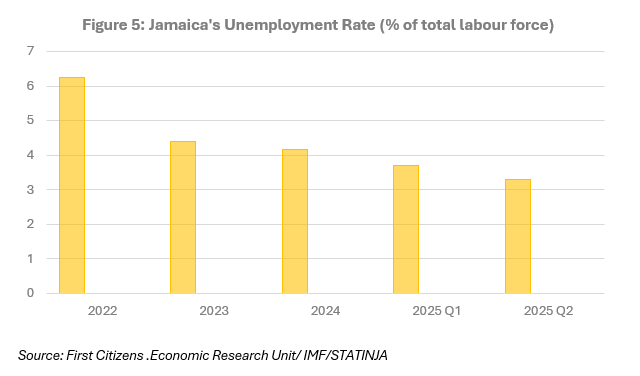

At the same time, labour market conditions have improved on the surface. Figures from the IMF indicate that the unemployment rate declined from 6.3% in 2022 to 4.4% in 2023, and further to 4.2% in 2024. Data from the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATINJA) shows that by Q1 2025, unemployment had reached 3.7% and declined further to 3.3% in Q2 (Figure 5). The labour force now stands at 1.49mn, with 1.44mn persons employed. The decline in unemployment has also been accompanied by lower underemployment and a reduction in the number of individuals remaining outside the workforce.

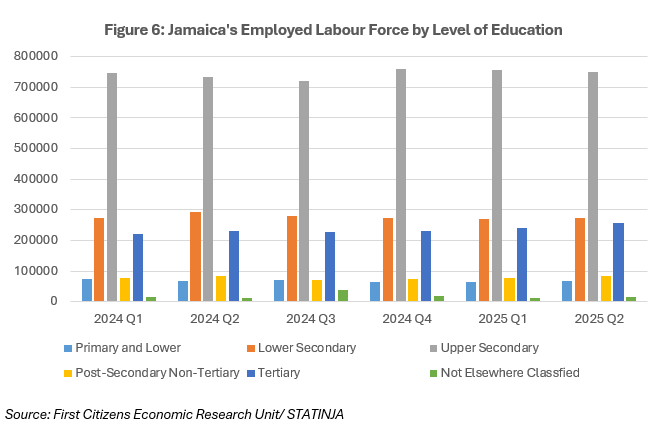

Yet beneath these headline improvements lies a deeper structural imbalance. According to STATINJA, as of Q2 2025, most employed Jamaicans, approximately 748,700, had attained only an upper secondary education, followed by 273,900 with lower secondary, and just 256,900 (Figure 6) with tertiary-level qualifications. This educational distribution suggests that job growth has largely occurred in lower- and mid-skilled segments of the economy, leaving high-skilled professionals underutilized or incentivized to migrate. In effect, while more Jamaicans are working, the labour market is not creating enough value-added, skill-intensive opportunities to retain the country’s best talent, contributing to the ongoing erosion of domestic human capital.

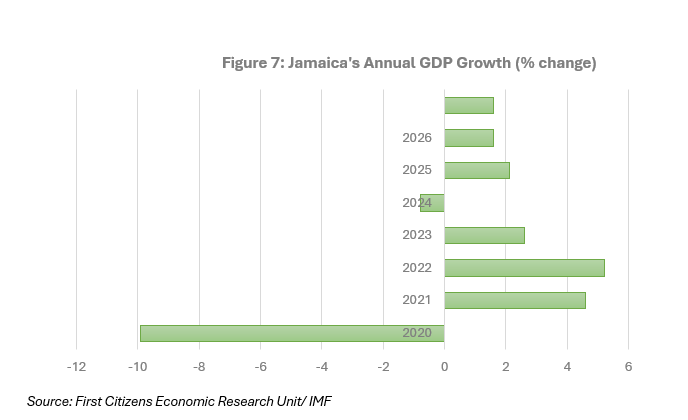

This imbalance is mirrored in the country’s growth path. Jamaica’s real GDP grew by just 2.6% in 2023, contracted by an estimated 0.8% in 2024, and is forecasted to rebound only modestly to 2.1% in 2025 and 1.6% in 2026 (Figure 7), according to the IMF. The persistence of sluggish growth despite record-low unemployment highlights a troubling disconnect, one that the Bank of Jamaica (BOJ) has aptly described as the “growthless jobs” phenomenon.

According to a 2023 BOJ report, this phenomenon stems from the structural saturation of Jamaica’s high-skilled labour segment. With the most productive workers already near full employment, additional hiring has largely absorbed lower-skilled individuals, resulting in modest productivity gains despite declining unemployment. This widening gap between employment and output reflects deeper issues—weaknesses in the education system and the ongoing emigration of skilled labour. Labour-intensive investments, especially those tied to Special Economic Zones (SEZs), have created jobs but contributed little to overall productivity. As labour market slack diminishes, the marginal output of newly employed workers continues to decline, exposing the limitations of a workforce that is not equipped to support transformative growth.

To address this imbalance, the BOJ urges greater investment in education and vocational training, alongside a reassessment of fiscal incentives that favour low-value-added industries. A shift toward high-value, skill-intensive sectors is seen as essential for strengthening long-term growth. Dr. Wayne Henry, Director of the Planning Institute of Jamaica echoes this, identifying the emigration of tertiary-educated professionals as a major structural challenge. He notes that existing retention strategies have fallen short, calling for a new framework to better harness skilled migration for national development.

Recommendations:

To curb the persistent outflow of skilled labour, Caribbean policymakers must prioritize structural reforms that enhance the domestic absorptive capacity for human capital. This requires aligning education systems with evolving industry needs, particularly in high-value sectors such as digital technology, renewable energy, medical services, and logistics. Beyond academic certification, the focus must shift toward labour market readiness and demand-driven training. Fiscal policy can also play a catalytic role: tax incentives and investment frameworks should be redesigned to favour skill-intensive enterprises that generate quality employment, rather than low-productivity sectors reliant on cheap labour. Additionally, strengthening intra-regional labour mobility under CARICOM can help optimize talent allocation across the region, reducing reliance on external migration pathways. Long-term, governments should view the diaspora not solely as a remittance source but as a strategic partner—leveraging knowledge transfers, targeted return programs, and remote work integration. These macro-level interventions are essential not only to retain talent but to foster a development model that maximizes the returns on public investment in human capital while supporting inclusive and sustained growth.

Conclusion:

In the Caribbean, the departure of talent is more than a personal decision—it is a collective economic cost. While growth may be visible in fiscal metrics and GDP charts, the quiet erosion of human capital tells a deeper story: one of stalled productivity, underperforming public systems, and delayed transformation. If the region is to fully realize its development ambitions, it must not only invest in people—but find ways to keep that investment at home. Until then, the Caribbean will continue nurturing the fruit, only to watch others reap the harvest.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.