Blue Economy: The Untapped Growth Frontier for the Caribbean

Commentary

Introduction

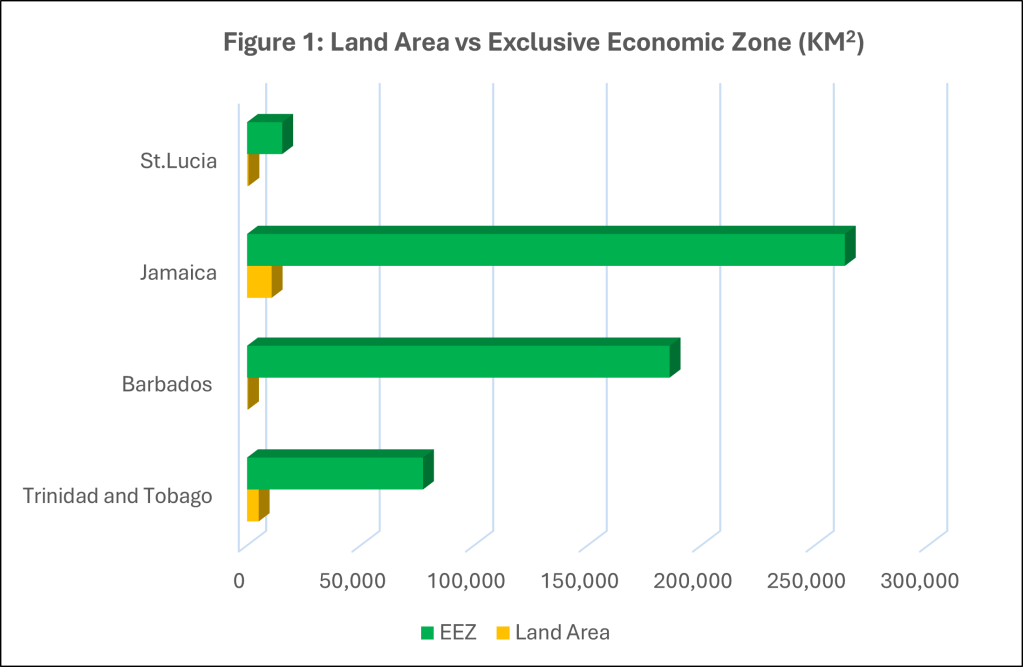

The Caribbean is frequently described as a group of small, land-constrained economies. While this description is technically accurate, it is economically incomplete. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), national economic space should be assessed not only by land area but by the full jurisdiction over productive resources. When viewed through this lens, many Caribbean states are not “small” at all. An Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is defined by the European Commission as an area where a coastal state assumes jurisdiction over the exploration and exploitation of marine resources in its adjacent section of the continental shelf, taken to be a band extending 200 nautical miles (370.4 km) from the shore. Across the region EEZs are often 10 to 50 times larger than land area, and in several island states, maritime space accounts for over 90% of total national territory. This reality fundamentally alters how development strategy should be conceived.

The concept of the blue economy, defined by the World Bank as the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ecosystem health, aligns directly with the Caribbean’s true geographic footprint. Yet, despite this alignment, economic planning, public investment, and statistical measurement across the region remain overwhelmingly land based. As climate shocks intensify and traditional growth engines face mounting constraints, this mismatch is becoming increasingly costly.

Why the Blue Economy Is No Longer Optional

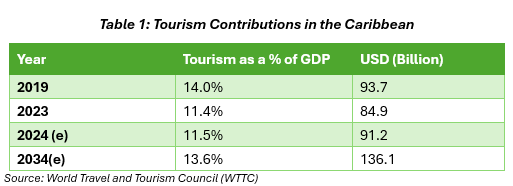

The urgency of adopting a blue-economy framework is rooted in hard macroeconomic constraints. Caribbean economies are among the most tourism-dependent in the world. The average contribution of the tourism industry in the Caribbean is estimated at 14% of GDP. Moreover, according to IMF country reports, tourism contributes between 20% and 90% of GDP across the region on a country level, when direct, indirect, and induced effects are combined. At the same time, many Caribbean countries face public-debt-to-GDP ratios above 70%, limited fiscal buffers, and high exposure to external shocks.

Climate change has introduced a new macroeconomic dimension. The IMF has repeatedly highlighted that small island states face disproportionately large output losses from climate events, with natural disasters capable of reducing annual GDP by 5%–10% in a single year. In this context, diversification is not a medium-term ambition, it is a near-term necessity. The blue economy offers one of the few diversification pathways that does not require additional land, large population growth, or heavy industrialisation.

Marine Assets Already Drive Core Economic Activity

Even without a formal blue-economy strategy, marine assets already underpin the Caribbean’s largest industries. Tourism, the region’s primary source of foreign exchange, is intrinsically marine-dependent. National tourism authorities and central banks consistently show that coastal and marine activities dominate visitor spending. Beaches, reefs, and nearshore waters form the core of the Caribbean tourism product.

Regional economic assessments estimate that over 70% of tourism activity in the Caribbean is coastal or marine-based, and that coral reefs alone support millions of annual visitors. Oxford Economics, in its tourism impact modelling used by governments, treats natural coastal assets as productive capital that directly influences visitor demand, length of stay, and average spend. When these assets degrade, tourism receipts fall – not immediately, but structurally.

Environmental Degradation as an Economic Cost, Not an Externality

Environmental degradation is often framed as a long-term ecological concern. In the Caribbean, it is an immediate economic cost. In the World Bank environmental assessments, untreated wastewater, marine litter, and coastal pollution impose hundreds of millions of US dollars in annual losses through reduced tourism appeal, damaged fisheries, and higher public clean-up costs.

Coral reef loss illustrates the scale of the risk. Regional marine assessments show that live coral cover in parts of the Caribbean has declined by more than 50% over recent decades. This loss weakens natural storm protection, increases coastal erosion, and reduces fish stocks. The IMF explicitly recognises natural ecosystems such as reefs and mangroves as “natural infrastructure,” noting that their degradation raises future public expenditure by increasing disaster-related damage and insurance costs.

Sustainable Fisheries: A Quantifiable Growth and Employment Pillar

Fisheries are often overlooked in macroeconomic analysis because their GDP share appears small. However, this understates their economic and social importance. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)and regional fisheries bodies, highlight that over half a million people in the Caribbean depend directly or indirectly on fisheries and aquaculture, with women representing a large share of employment in processing and marketing.

In several Caribbean economies, official statistical offices report annual marine fish landings ranging from 1,000 to over 20,000 tonnes, depending on country size and resource base. These figures represent not just food supply, but income generation, import substitution, and export potential. The FAO estimates that global seafood demand has more than doubled since the 1960s, with aquaculture now accounting for over 50% of global aquatic animal production. This trend presents a clear opportunity for Caribbean states to expand sustainable aquaculture under strong regulatory frameworks.

From a balance-of-payments perspective, strengthening domestic fisheries and aquaculture can reduce food import bills, which account for 15–30% of total merchandise imports in many Caribbean economies. This has direct implications for foreign-exchange stability and inflation management.

Food Security and Price Stability Benefits

Food security is increasingly a macroeconomic issue. The IMF has highlighted that small island states are especially vulnerable to global food price shocks due to high import dependence. During recent global supply disruptions, Caribbean food inflation exceeded headline inflation in several countries, contributing to real income erosion.

A blue-economy strategy that strengthens fisheries, expands aquaculture, and integrates local seafood into tourism supply chains can dampen these pressures. By shortening supply chains and increasing domestic protein availability, countries can reduce exposure to imported inflation while supporting rural and coastal employment.

Maritime Services and Ports: The High-Scale Opportunity

While fisheries provide inclusive growth, maritime services offer scale. The Caribbean sits astride major global shipping routes linking North America, South America, Europe, and the Panama Canal. According to national port authorities and transport ministries, several Caribbean ports handle hundreds of thousands of containers and millions of tonnes of cargo annually, supporting trade, energy exports, and cruise tourism.

The OECD and World Bank consistently find that port efficiency is a key determinant of trade costs. Their analysis shows that a 10% improvement in port efficiency can reduce trade costs by up to 1.5 %, with outsized effects in small open economies. For the Caribbean, modernising ports through digital customs, faster turnaround times, and improved maritime services can lower import prices, improve export competitiveness, and attract regional transshipment activity.

Crucially, maritime services generate higher-value employment in logistics, engineering, IT systems, compliance, and finance, diversifying the labour market beyond tourism and public services.

Tourism’s Structural Shift: From Volume to Value

Tourism will remain central to Caribbean economies, but its structure must evolve. Tourism statistics show that while arrivals have recovered in many Caribbean destinations, average spend per visitor has not always kept pace, and import leakage remains high. The IMF has repeatedly warned that high-volume tourism models can strain infrastructure and ecosystems without delivering proportional economic benefits.

A blue-economy approach prioritises value over volume. Eco-coastal tourism, marine recreation, yachting, and dive tourism command higher spending and align incentives with conservation. According to tourism satellite accounts used by governments, higher-end marine tourism generates stronger linkages to local services and lower environmental pressure per dollar earned.

Marine protected areas and reef restoration projects, when integrated into tourism strategy, can enhance destination competitiveness while reducing long-term disaster costs. These initiatives can also be partially self-financing through visitor fees and tourism levies, reducing fiscal strain.

Marine Renewable Energy and Long-Term Resilience

Energy costs remain a structural constraint across much of the Caribbean. IMF country reports show that fuel imports account for a significant share of merchandise imports in energy-importing states, contributing to current-account deficits and inflation volatility. While solar and onshore wind have expanded rapidly, marine renewable energy broadens the long-term option set.

Offshore wind, wave energy, and ocean-based systems can complement existing renewable strategies, particularly where land availability limits scale. Although capital-intensive, these investments can reduce fuel import dependence, stabilise electricity costs, and improve energy security. Over time, these effects feed into stronger external balances and lower macroeconomic volatility.

Financing the Blue Economy: From Concept to Capital

Financing remains the most binding constraint. Caribbean public debt levels limit fiscal space, making private and blended finance essential. The World Bank and IMF have both emphasised that access to capital depends on credible project pipelines, strong governance, and measurable outcomes.

Blue bonds, public-private partnerships, and blended-finance structures are increasingly used to fund sustainable ocean industries globally. These instruments work when projects generate predictable cashflows and are supported by transparent reporting. This places renewed importance on national statistical offices and line ministries producing consistent data on fisheries output, port throughput, tourism linkages, coastal damage, and environmental indicators.

Conclusion

The Caribbean’s vulnerability to climate change is undeniable, but vulnerability does not have to define its economic future. Resilience is built not only through buffers, but through diversification and structural transformation. The blue economy offers precisely that an opportunity to align geography, sustainability, and growth.

With ocean territory that dwarfs land area, marine assets that already underpin a significant share of GDP, and growing global demand for sustainable ocean investment, the Caribbean is uniquely positioned to lead rather than follow.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment, or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.