The Enemy of My Enemy Is My Friend – Tariff Edition

Commentary

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend” is an ancient proverb that suggests that two parties, despite not being naturally aligned, may find common cause and cooperate against a shared adversary: in this instance the U.S. This strategy of forging unlikely alliances geopolitically with the shared goal of opposing a common “enemy” for the benefit of the allied parties is not new. For example, this idea was employed during World War II when the Western Allies and the Soviet Union recognized that working together to combat the threat of the Nazis was the best solution.

Since taking office for the second time, President Trump and his administration has remained focused on levelling perceived trade imbalances between the U.S. and its trading partners with the goal of strengthening its international economic position, protecting its national security and driving economic growth for the American people. The administration sought to utilize tariffs as a means of achieving these goals, however this approach was not received lightly by its trading partners.

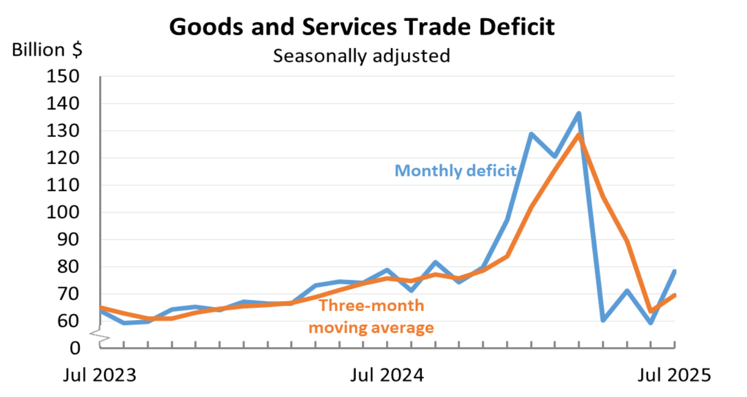

The U.S. is the world’s second largest trading nation, behind only China whose exports and imports of goods and services in 2024 was valued at over USD6.1 trillion. The U.S. total imports in 2024 were valued at USD3.36 trillion, according to the United Nations Comtrade database on international trade, where the main import partners were Mexico, China and Canada. Total exports were valued at USD2.06 trillion, leaving the U.S. with a trade deficit of USD1.29 trillion. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that, so far this year, the U.S. trade deficit in goods and services has grown by USD175 billion dollars, or 50.4%, compared to the same period last year. Exports increased by USD103.1 billion dollars (5.5%), while imports rose by USD257.5 billion dollars (10.9%). In July 2025 alone, the trade deficit was USD78.3 billion dollars, which is USD18.1 billion dollars higher than the USD60.2 billion dollar deficit in June.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Census Bureau

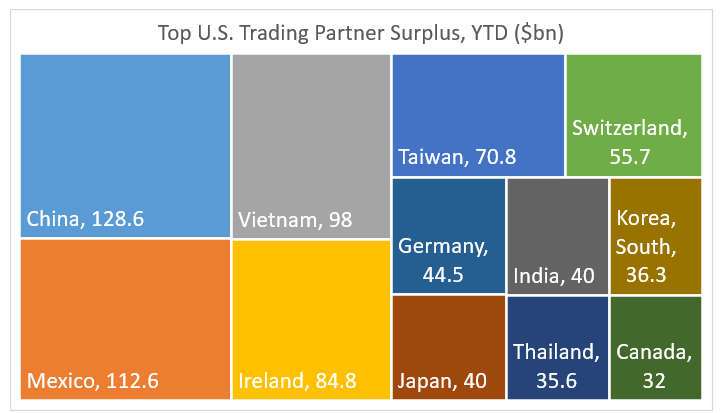

On April 2, 2025, President Trump invoked the IEEPA (International Emergency Economic Powers Act) to announce his initial set of “reciprocal tariffs” on imports from all countries not subject to separate sanctions, dubbing it “Liberation Day”. A baseline 10% tariff as well as higher rates for dozens of nations that run trade surpluses with the U.S. took effect on April 5, noting that all tariffs announced thus far have been on goods only with no mention of services. The White House explained that this strong action shows the President’s commitment to protecting the U.S. from outside economic threats, making trade fairer for American workers, and supporting the country’s defence industries. On a goods only basis, year-to-date the top three trading partners that currently have trading surpluses with the U.S. are China at USD 128.6 billion, Mexico with USD112.6 billion and Vietnam at USD98 billion.

Source: US Census Bureau, FCIS Investment Research & Analytics

In the wake of the U.S. wave of tariff threats and impositions, a subtler yet significant consequence began to unfold, one that initially escaped widespread attention. Nations around the world, faced with mounting uncertainty, began to revisit existing trade agreements and rekindle strained partnerships, not merely as acts of diplomacy, but as strategic efforts to shield their economies from potential disruption. Aligned with the principles of social balance theory, this pivot toward alternative alliances was a natural and foreseeable response, with countries gravitating toward one another to restore equilibrium, safeguard economic stability, and advance mutual interests in an increasingly polarized global trade environment.

United Kingdom and European Union

Nearly eight years after “Brexit”, Donald Trump’s disruption of the global trade landscape prompted both the United Kingdom (U.K.) and the European Union (EU) to set aside past tensions and reassess their relationship. Brexit refers to the U.K.’s decision to leave the EU, first triggered by a narrow 51.89% “leave” vote in the 2016 referendum. Although the official separation was finalized in December 2020, it did not completely sever ties between the U.K and the region, but it did significantly reshape their trade dynamics.

The Brexit campaign gained momentum during the 2015 migration crisis, which was largely driven by the Syrian Civil War. At its core, the campaign promised the U.K. a return to sovereignty, particularly over its borders and immigration policies, which many voters found appealing. However, the decision to leave the EU was controversial. Critics argued that the economic and political benefits of remaining in the EU far outweighed the drawbacks of leaving, especially given that much of the campaign was fuelled by fears surrounding the EU’s policy on the free movement of people across member states.

On May 19, 2025 the U.K. and the EU reached a new set of agreements, reshaping their “post-Brexit” trade relationship, as well as reigniting trade relations. This renewed partnership comes at a critical time, as the U.S. continues to disrupt global trade stability. A central feature of the deal grants European fishing boats a further 12 years of access to U.K. waters in exchange. In return, the EU agreed to ease trade barriers, including reducing checks on food exports from the U.K. to the continent. This agreement represents the most significant reset of U.K.–EU trade ties since Brexit was finalized in 2020 and follows years of tension and negotiation.

Another notable feature of the trade agreement is the inclusion of e-gate access for British citizens, allowing them to use EU electronic passport gates when traveling through European countries. However, the final decision to permit this access rests with each individual EU member state. Beyond travel convenience, the deal also spans several critical areas, including defence and security cooperation, carbon and energy frameworks and a new youth mobility scheme aimed at enhancing cultural and educational exchange.

The mending of this once-strained partnership marks a positive turning point for both the U.K. and EU economies. It not only strengthens bilateral ties but also provides a measure of protection against potential economic fallout stemming from ongoing U.S. tariff threats. This is underscored by data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which estimates that roughly 1.4% of the U.K.’s GDP is linked to goods and services traded with the U.S., highlighting the importance of reinforcing other trade relationships in a shifting global landscape.

European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and Mercosur bloc

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which is an intergovernmental organisation, comprising Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland, was established to promote free trade and economic cooperation among its members, both within Europe and globally.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Mercosur, the Southern Common Market, was formed in 1991 and includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, with several other South American nations holding associate member status.

Although trade negotiations between EFTA and Mercosur had been ongoing for several years, talks gained renewed momentum in 2025 amid rising global trade tensions triggered by the U.S.’ unpredictable tariff policies. The final agreement was reached in July 2025 during the Mercosur Summit in Buenos Aires. This historic pact creates a free trade area encompassing nearly 300 million people and a combined GDP of USD4.3 trillion.

The deal offers significant benefits by enhancing market access—covering over 97% of bilateral trade—which is expected to boost opportunities for both businesses and consumers. Most notably, almost all Swiss exports to Mercosur will be fully exempt from customs duties once the transition period ends. Beyond tariff reductions, the agreement emphasizes sustainable trade practices, including Brazil’s landmark commitment to using clean electricity in service sectors—a first for any of its trade deals. By removing trade barriers and encouraging regulatory alignment, the EFTA-Mercosur agreement opens the door to substantial new economic and trade opportunities across both regions.

BRICS

BRICS, the intergovernmental organization comprising ten countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, the UAE and Indonesia, like other economic trade associations, aims at greater economic and geopolitical integration among member states. At its most recent summit in July 2025, the bloc renewed its commitment to strengthening these ties, with a strong push toward finalizing the Strategy for BRICS Economic Partnership 2030.

One of the central themes of the summit was the growing threat posed by the U.S. aggressive tariff policies, particularly under Donald Trump’s renewed leadership. BRICS nations sought to present a unified stance in response, even as they acknowledged differences in their individual strategies for managing the fallout. Brazil’s President strongly defended the sovereignty of the bloc’s members and denounced the U.S. tariffs, especially as Brazil faced a 50% tariff beginning August 1, 2025. The group collectively warned that such protectionist measures could stifle global trade, disrupt supply chains and intensify economic uncertainty at a time when global cooperation is more important than ever.

Many of these revised or fast-tracked trade agreements might have unfolded at a far slower pace — or perhaps not at all — were it not for the global trade shock. That announcement served as a powerful catalyst, compelling nations to urgently re-evaluate their trade strategies, renegotiate existing terms and realign partnerships. In doing so, it fundamentally reshaped the global economic landscape, as countries sought not only to safeguard their interests in the present but also to hedge against the growing unpredictability of future U.S. trade policy.

Investment Implications

These renewed and deepening trade agreements will help in stabilizing global markets by reducing the uncertainty caused by Trump’s elevated, reciprocal tariffs. While initial trade tensions introduced risks for investors, ongoing agreements support long-term investment planning by promoting smoother trade flows and regional/global integration. This added stability helps offset some of the economic drag from the U.S. tariff policy—both the direct and indirect impacts via market uncertainty and stock volatility. Stronger trade agreements can enhance GDP growth and trade volumes, particularly benefiting countries with close economic ties or those adapting supply chains to the new trade environment. In response to tariff-driven volatility, investors are advised to maintain diversified portfolios with a blend of equities, bonds, and alternative assets. Tactically reducing overexposure to U.S. sectors vulnerable to tariffs—such as technology, materials, autos and retail—and reallocating toward defensive or domestically-oriented industries can enhance portfolio resilience. International equities, real assets, infrastructure, and commodities like gold offer both diversification and protection against inflation and geopolitical risks. Active management and a strong focus on valuation are crucial in navigating this evolving environment. While not all companies or sectors will be equally affected by trade disruptions, focusing on quality assets and gradually rebalancing portfolios can help investors capitalize on new opportunities while mitigating downside risks.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment, or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.