The Economics of the World Cup

The Economics of the World Cup

The FIFA World Cup is one of the most prestigious sporting mega-events in the world and is not only considered an honor to host but is assumed to be highly profitable. Historically, the exposure has brought to host nations increased foreign trade and tourism, additional jobs, and has paved the way for new infrastructural development which potentially holds short-term and long-term economic gains… but at what cost? Economists over time have debated whether the cost significantly outweighs the benefits for the host nation, but it seems to vary from country to country.

To successfully become a host nation, a country must submit a proposal listing why it makes financial sense for the governing body (FIFA), as well as how the host country intends to achieve the goal of widening the sport’s global reach. The two main categories used by FIFA to determine qualification for hosting are infrastructural and commercial factors along with other strict criteria which are weighed by varying levels of importance. The most critical of these considerations is the construction of stadiums which is the most significant undertaking.

Despite the high cost associated with this, it is considered a reasonable investment as not only can these sporting facilities continue to generate revenue from future events but the non-sports infrastructure such as expanded transportation networks and new business areas boost the neighborhoods surrounding stadiums for years to come. Stadiums like the Allianz Arena in Munich and Wembley Stadium in London, have become iconic landmarks of host cities, enhancing their image and attracting tourists and investors alike. Some other developed host countries like Germany and France continue to host top football leagues and stadiums are used by domestic clubs as their home stadiums which continue to turn over revenue over the years from ticket sales.

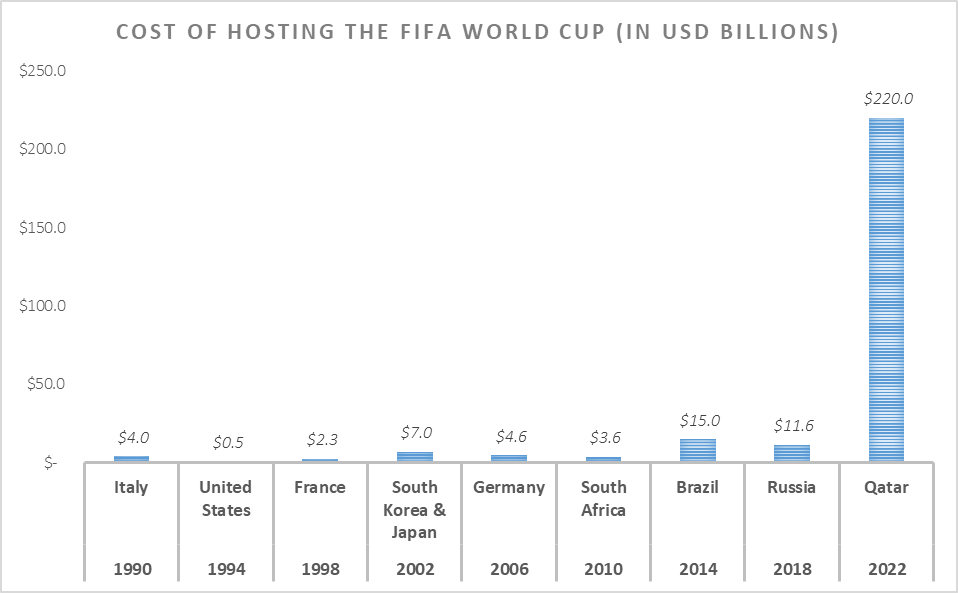

Developing countries however spend significantly more money on construction and reap less benefits than developed countries and usually incur massive debt. In the case of Brazil’s 2014 World Cup, estimates indicate that USD11.6 billion was spent on constructing transport infrastructure, hotels, and the Mane Garrincha stadium which is now used as a bus depot. Local protestors at the time criticized both the government and FIFA for the allocation of funds towards football stadiums rather than social services for the people. Likewise, in South Africa, business areas located in stadium precincts eventually became segregated (Hendricks et al., 2012) as there was low usage after the World Cup.

One of the biggest short term economic benefits of hosting the World Cup is the increase in tourism as the sudden influx of fans directly stimulates above-average spending on hotels, restaurants, tourist attractions, and consumption in retail. Instead, longer-term economic impacts may take the form of “indirect” or “intangible” factors like the ‘feel-good effect’ on citizens, and the Cup’s effect on the international perception of a host country.

The ‘feel good’ atmosphere created during the World Cup makes citizens happier and prouder than they might otherwise be, and therefore more willing to consume (Allmers & Maennig, 2009). In studies of the 2006 German World Cup, it was found that the average Willingness to Pay (WTP) of citizens increased from €4.26 per person to €10.0 after the World Cup (Heyne et al.). Similarly, Kavetsos and Szymanski (2008) reconfirmed the theory that hosting mega-sport events like the Olympic Games and the World Cup can elevate the overall happiness of citizens.

Hosting the World Cup can be a branding process for the host country and helps to attract tourists and additional capital investments while enhancing the perception of the country. The perception of Germany, for instance, has been enhanced in other countries according to Allmers and Meannig (2009), where “The erstwhile image abroad of Germany as ‘hard and cold and not a nation much associated with warmth, hospitality, beauty, culture or fun’ was improved through the World Cup”. This enhanced national image paves the way for future growth in tourism as television viewers may have an interest in visiting the country and visitors can decide to return. The degrees of image enhancement may vary but it can potentially be particularly beneficial for developing countries.

Qatar is currently on the world stage and hosting the 2022 World Cup is its catalyst to propel development and achieve its 2030 National vision to transform the nation into a global society and provide a higher standard of living. The government has reportedly spent over USD229 billion which is roughly 100% of Qatar’s GDP, making it the most expensive World Cup in history, and is expected to bring in USD17 billion in revenue for their economy, according to official estimates. However, how much revenue they reap hinges on various factors. Notably, much of the profit generated from the games will be returned to FIFA, who also gain tax breaks on merchandise, food, and other purchases from their associated brands. Past research suggests that the costs associated with hosting a World Cup outweigh the benefits. Economists Robert Baade and Victor Matheson found that for the 1994 US World Cup, ‘host cities experienced cumulative losses of up to USD9 billion – in contrast to the USD4 billion gain they had expected’. This is largely due to the high maintenance costs of newly constructed infrastructure after the competition is over or the abandonment of the structures yielding no returns.

With the goal of increasing tourism to six million tourists per year by 2030 from two million in 2019, Qatar has made significant investments in infrastructure, including developing cutting-edge stadiums, modern transit systems, and expanding its airports. Currently, Fitch Solutions predict that Qatar’s real GDP growth will more than triple in 2022 to 5.2% from the meager 1.5% in 2021, only to decrease to 2.8% the following year as the tournament’s economic boom fades into obscurity. Beyond the World Cup, Qatar’s fiscal and debt situation is anticipated to improve as Fitch predicts that its fiscal surplus will increase from 0.3% of GDP in 2021 to 9.9% of GDP in 2022, primarily as a result of higher-than-anticipated hydrocarbon revenues and an increase in non-hydrocarbon revenues brought on by a spike in tourist arrivals and an increase in corporate tax revenues. In the medium term, Qatar’s debt situation will also improve significantly, as it is anticipated that higher gas prices would enable the nation to maintain healthy fiscal surpluses in the years to come. Fitch predicts that overall, Qatar’s debt-to-GDP ratio will decline from a peak of 71.6% in 2021 to an average of 36.0% in 2031.

Qatar is an energy-based economy and economic and fiscal performance is heavily dependent on the energy markets, which remains very volatile. Given this vulnerability, the significant expenditure associated with hosting the World Cup necessitates post-tournament sustainability measures if Qatar is to benefit in the long-term and to avoid producing transient economic gains like those experienced by mega-sporting hosts in the past.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report