The Global Food Crisis

Insights

Instead of a post-pandemic recovery phase, global economies are now experiencing further downward revisions to growth prospects due to a complex combination of new challenges. The United Nations food agencies – the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and World Food Programme (WFP) have issued warnings of looming food crises, driven by conflict, climate shocks, and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is being exacerbated by the ripple effects of the war in Ukraine that has accelerated food and energy prices globally. These dynamics are causing drastic income losses among the poorest communities and are straining the capacity of national governments to fund social safety nets, provide income-supporting measures, and to sustain import of essential goods, all increasing the risk of poverty, food insecurity and political instability. These risks now amplify credit risks specifically for emerging markets.

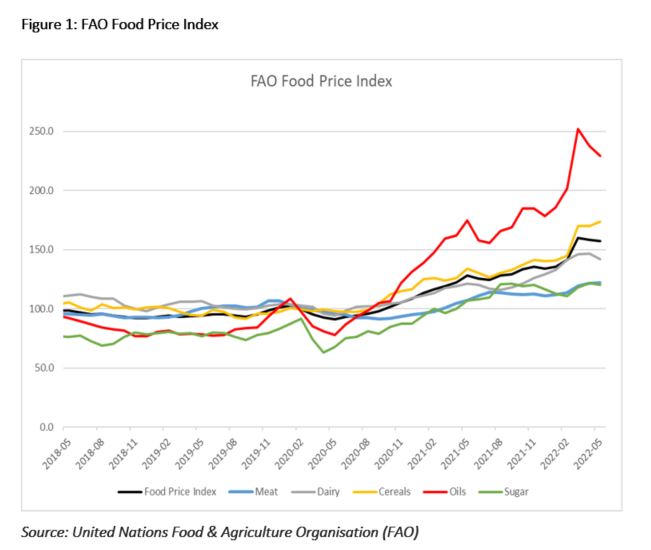

The consequences of the Russia-Ukraine conflict can be felt across the globe through exacerbated inflationary pressures from disruptions to commodities and food supplies as both countries are important exporters of food, petroleum, and fertilisers. According to the WFP, Russia and Ukraine supply 30% of globally traded wheat, 29% of the barley, 20% of the maize and 75% of the sunflower oil. With its invasion, Russia has seized wheat, bombed silos, and blocked many railways disrupting Ukrainian exports which has consequently increased the price of the grain that supplies one-fifth of all calories consumed by humans. The Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) food price index, which tracks international prices of the most globally traded food commodities, reached its all-time high of 159.7 points in March, up from 141.1 points the previous month. While it decreased slightly to 157.4 points in May, the ongoing effect of the war will continue to push prices to new highs.

India, the second-largest producer of wheat globally attempted to cater to the shortfall but due to erratic weather conditions, production levels were devastated, proving that an even more persistent threat to global food security is climate change. Unpredictable and unforeseen weather events can wipe out harvests, extreme heat can destroy livestock and not only create an unsafe environment for farm workers but unfavourable farming conditions, while other natural disasters and flooding can affect the infrastructure needed to transport food items to the vulnerable. According to the deputy director of WFP’s emergencies division, “Climate change is not the only contributing factor, supply chain issues and economic instability linked to the coronavirus pandemic have raised costs for fuel, fertiliser, shipping and other agricultural inputs.” This makes it even more difficult for other nations to buffer the effects of this looming food crisis.

The most vulnerable, especially in countries that rely heavily on food imports are the most at risk to the crisis. Data from the IMF shows that while food costs account for 17% of consumer spending in advanced economies, it accounts for approximately 40% in sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, as food prices increase, consumers must allocate a greater portion of their income on food, thereby pushing them further into poverty to stave off hunger. The World Bank warns that every percentage point increase in global food prices will push 10 million people more into extreme poverty around the world. Additionally, global hunger levels are alarmingly high. According to the Global Report on Food Crises 2022, approximately 193 million people in 2021 were acutely food insecure and in need of urgent assistance across 53 countries/territories. This represents an increase of 40 million people compared to the previous high reached in 2020. The outlook for global food insecurity in 2022 is expected to deteriorate further relative to 2021.

Further, food shortages coupled with price increases have inevitably created social unrest as individuals who were already frustrated, are pushed over the edge by rising costs in countries that are already grappling with hunger issues. Recent unrest has also highlighted the dangers and many protests have erupted over gas and food shortages. In Pakistan, double-digit inflation has weakened the Prime Minister’s support, forcing him to resign, while violent protests were sparked by increased food and fuel costs in Peru. The current political turmoil in these countries serves as an unsettling example for countries dealing with similar circumstances. There are even comparisons between the current situation and the Arab Spring revolts, a series of anti-government riots in the Middle East that began in 2010 in response to a rise in food prices. Even more developed economies may not have the tools needed to cushion the blow of soaring prices as seen in Europe where protesters have already taken to the streets demanding higher wages to counter inflation.

Accompanying the global food shock is the amplification of credit risks for emerging markets, placing pressure on sovereign ratings. According to S&P, “Rising energy and food prices represent yet further balance-of-payments, fiscal, and growth shocks to the majority of emerging markets. This intensifies strains on their public finances and credit ratings, which are already impacted negatively by the global pandemic.” In a report, S&P Global also stated that while many of the sovereigns most vulnerable to increasing food prices already had low credit ratings, the negative economic or political consequences of the food shock could lead to further downgrades.

Serious implications lie ahead for Caribbean nations that rely heavily on imports for the majority of their food consumption. This will have an especially negative impact on low-income and vulnerable households already suffering from the repercussions of COVID-19. The CARICOM Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security and Livelihoods Impact Survey, conducted in collaboration with the World Food Programme, began documenting the impact of COVID-19 on food security and livelihoods in 22 English- and Dutch-speaking Caribbean nations and territories. According to the survey done in February 2022, there has been an overall rise of 1 million people who are food insecure since the pandemic began. The number of persons who are severely food insecure has climbed from 482,000 in February 2021 to 693,000 in February 2022, accounting for approximately 10% of the population. Severe food insecurity has risen by 44% in the last year and by 72% since the first set of surveys in April 2020. According to WFP “as an import-dependent region, the Caribbean continues to feel the socio-economic strain of COVID-19 which is now being compounded by the conflict in Ukraine. With most COVID-19 assistance programmes having concluded, many families are expected to face an even greater challenge to meet their basic food and other essential needs in the months to come.”

Post-pandemic global demand, extreme weather, tightening food stocks, high energy prices, supply chain bottlenecks and export restrictions have been straining the food market for two years, but the combined impact exacerbated by the war compounds the implications for global livelihoods. Beyond the immediate humanitarian impact, comprehensive solutions are needed, consistent with sound fiscal management.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have not acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.