The Next Chapter of Global Finance: BRICS+ and the Emerging Market Surge

Insights

From Acronym to Influence

When economist Jim O’Neill introduced the term BRIC in 2001, it was never intended to describe a political bloc. It was simply a way to highlight four large, fast-growing economies that he believed would reshape global economic growth: Brazil, Russia, India and China. South Africa joined in 2010, forming BRICS, and years later the group expanded again. In 2024, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates became members. Indonesia followed in 2025. With this expansion, the coalition is now known as BRICS+, representing a wider and more diverse set of emerging markets (EMs).

What started as an investment acronym has grown into a geopolitical and financial alliance with ambitions that extend far beyond growth forecasts. Today, BRICS+ is increasingly seen as an economic counterweight to advanced Western economies, with significant influence over trade, commodities, financial flows and global institutions. In the early 2000s, the BRICS nations symbolized rapid industrial growth and rising economic potential, housing nearly half the world’s population, holding abundant natural resources and expanding far faster than developed markets.

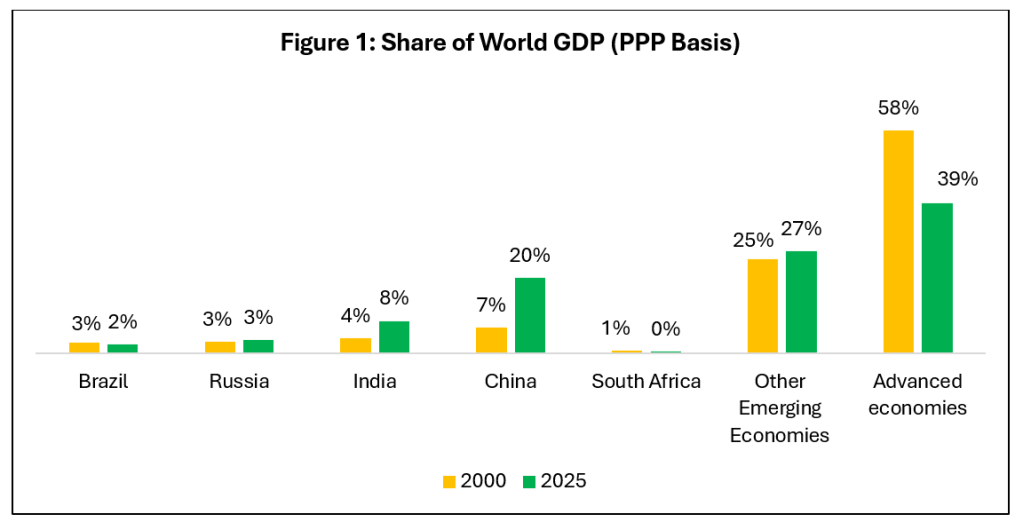

Their expanding economic weight became even more pronounced when measured using Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)—a method that adjusts for differences in living costs and price levels to provide a more accurate comparison of economic size. For example, if a basket of goods costing USD100 in the United States (US) costs TTD700 in Trinidad and Tobago, the PPP exchange rate would be 7:1, even if the market exchange rate differs. Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund rely on PPP because it better reflects real purchasing power and domestic consumption capacity. Viewed through this lens, China surpassed the US in economic size several years ago, and India has now risen to third place globally.

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF)

How China, India and Other Emerging Markets Rose

China’s ascent was anchored in an export-led industrialization strategy, reinforced by substantial foreign direct investment inflows and propelled decisively by its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Membership in the WTO marked a pivotal turning point, compelling China to modernize its economic framework, adopt global trade disciplines, and open its markets to international competition. In return, the country strategically deployed incentives such as tax concessions and preferential treatment to attract foreign investors, particularly in manufacturing. As capital and technology poured in, China’s share of global exports expanded swiftly, driven by a surge in high-value, technology-intensive goods. Productivity gains accelerated as firms integrated imported intermediate inputs into their production processes and responded to heightened competitive pressures. These forces collectively transformed China into the centrepiece of global supply chains, a role that earned it the enduring title of “the world’s factory.”

India’s economic rise, by contrast, emerged from a fundamentally different growth model anchored in the services sector. The rapid expansion of information technology, business process outsourcing, and fintech industries propelled services to contribute more than half of national output. India’s growth drew strength from a rising middle class, expanding urbanisation, and strong domestic consumption, while simultaneously capturing significant global market share in digital services, software development, and business solutions. Successive waves of economic reforms—particularly in trade liberalisation and foreign investment frameworks further strengthened India’s international competitiveness and deepened its integration into global value chains.

Together, China’s manufacturing-driven export surge and India’s services-led expansion form the twin pillars of BRICS’ economic dynamism. Their distinct yet complementary growth trajectories have powered global capital flows, stimulated international trade, and served as critical engines of corporate earnings and economic momentum across EMs.

Emerging Markets Advance into the Financial Mainstream

As BRICS economies expanded, global investors gradually shifted from viewing EMs as peripheral, speculative bets to seeing them as essential components of long-term growth portfolios. Capital began flowing steadily into BRICS and other developing economies through foreign direct investment, increased cross-border lending, and surging portfolio allocations to stocks and bonds.

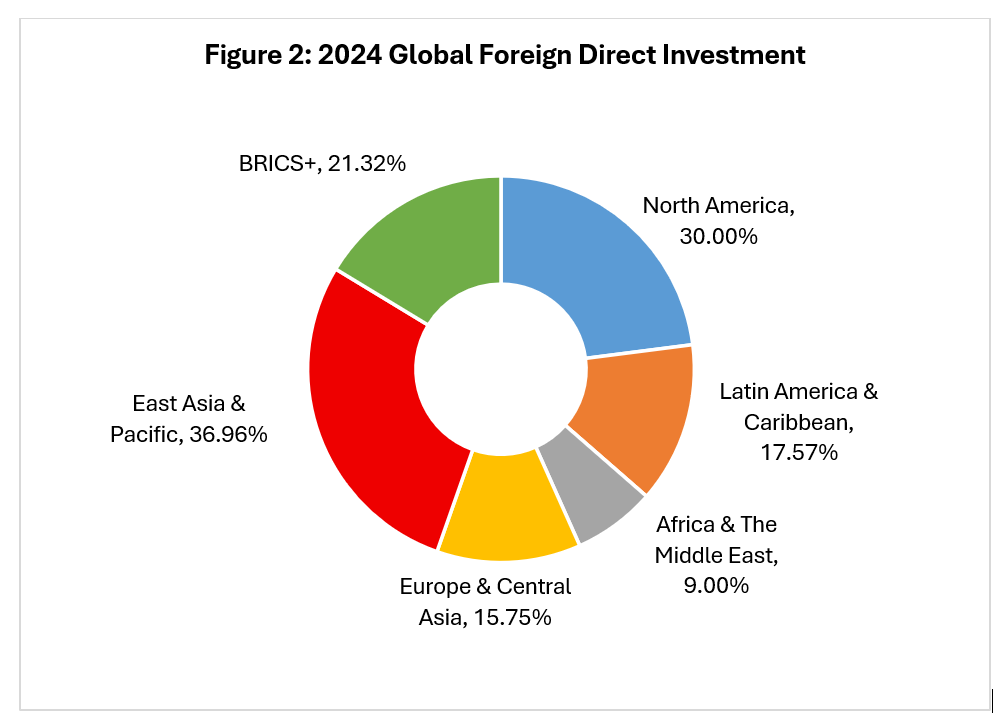

Local currency debt markets deepened, financial systems matured, and major asset managers built entire suites of emerging-market exchange-traded funds to meet rising investor demand. The integration of EMs into the global financial architecture became one of the defining investment trends of the 21st century.

Source: World Bank Group

BRICS+ and the 2025 Surge in Emerging Market Equities

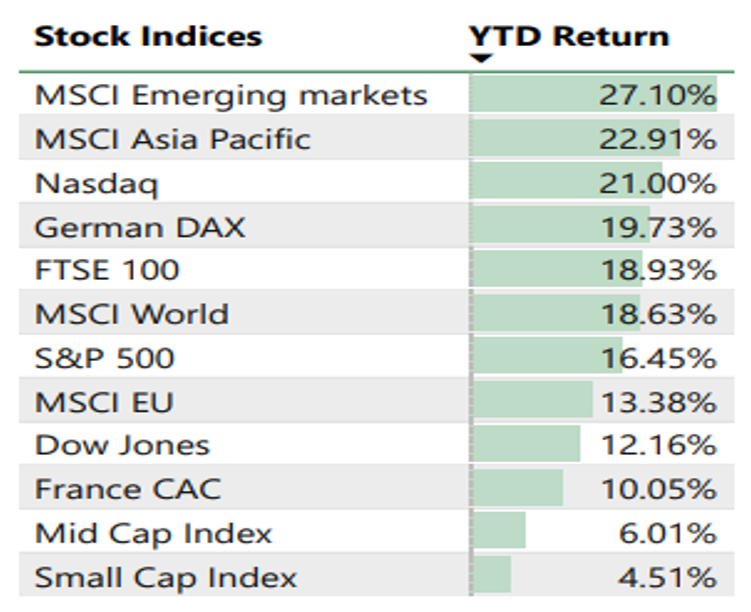

The year 2025 has been particularly notable for BRICS+ and EMs more broadly. As illustrated in Table 1, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, which is heavily weighted toward BRICS+ economies, has outperformed major developed-market benchmarks such as the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq. Behind this outperformance lies a combination of macroeconomic, currency, and corporate-specific drivers that underscore the shifting balance of global growth.

One of the most influential factors has been a softening US dollar. With the US markets anticipating Federal Reserve rate cuts, and policy uncertainty weighing on market sentiment, the dollar has weakened relative to many emerging-market currencies. This dynamic matters because a softer dollar typically boosts EM asset performance: it eases debt burdens for countries and companies that borrow in US dollars, encourages capital flows into riskier markets, and enhances returns for foreign investors once earnings are converted back into US currency. The currency backdrop in 2025 has therefore provided a meaningful tailwind for EM equities.

Equally significant has been the strength of corporate earnings across the EM world. China has seen solid performance in sectors such as technology, electric vehicles, and consumer goods. South Korea and Taiwan, long central to global technology supply chains, have benefited from a robust rebound in the cyclical semiconductor and electronics sectors. India’s financial services, consumer-oriented industries, and technology services firms continue to grow rapidly alongside a booming domestic economy. Many of these companies have been able to expand margins thanks to efficient cost structures, resilient domestic demand, and their ability to compete internationally. In short, EM corporates are no longer just low-cost manufacturers, they are global leaders in innovation, scale, and demand growth.

Underlying all of this is the broader growth differential between emerging and developed economies. According to the IMF, EMs are expected to grow at a 4.2% pace in 2025, compared with just 1.8% for advanced economies. Faster growth supports corporate revenues, fuels expanding consumer markets, and reinforces the long-term investment case for EM equities. Countries like India, Indonesia, and Vietnam are further benefiting from supply-chain diversification, expanding manufacturing bases, and large-scale urbanization trends. These forces collectively strengthen the emerging-market growth narrative and explain why investors have been rotating into BRICS+ and other EMs.

Reshaping of the Global Commodity Landscape

BRICS+ has reshaped global commodity markets more than any other area of finance. China’s rapid industrialisation made it the world’s largest buyer of key metals, giving its economic cycles enormous influence over global prices. India’s fast-growing cities and rising energy needs have made it a major driver of demand for oil, gas, and construction materials. At the same time, many BRICS+ countries are among the world’s leading commodity exporters—Brazil in agriculture and iron ore, Russia in energy, South Africa in precious metals, and the Gulf states in oil.

Because some BRICS+ members are major consumers while others are dominant producers, the bloc now plays a powerful role in shaping global commodity price cycles. Markets around the world increasingly move in response to economic signals from Beijing, New Delhi, and Brasília. China’s manufacturing data shift metal prices, India’s energy demand influences oil benchmarks, and production changes in Russia or the Gulf can sway global inflation and financial stability. In effect, the economic pulse of BRICS+ has become deeply intertwined with global commodity pricing and global market dynamics.

A Multipolar Financial Future Takes Shape

The transformation of BRICS+ from an investment thesis into an economic and geopolitical force represents one of the most important structural shifts of the 21st century. With China and India anchoring global demand, resource-rich members shaping supply dynamics, and new entrants from the Gulf strengthening financial and geopolitical weight, BRICS+ now plays an increasingly decisive role in determining the rhythm of global growth. As the bloc continues to formalize cooperation in areas such as payments systems, reserve currency diversification, and investment frameworks, its collective footprint will only grow more significant.

For investors, this evolving landscape presents both opportunity and complexity. The rise of BRICS+ broadens the universe of high-growth markets, offering access to rapidly expanding consumer bases, vast infrastructure pipelines, and strategically important commodity sectors. Exposure to BRICS+ economies—through equities, sovereign and corporate debt, commodities, and thematic strategies such as energy transition or digitalization—can enhance portfolio diversification while tapping into structural growth drivers unavailable in more mature markets. As the bloc’s global relevance strengthens, investors who position themselves thoughtfully stand to benefit from new channels of economic dynamism, deeper capital markets, and long-term value creation shaped by the world’s fastest-growing economic engines.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment, or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.