Caught in the Crossfire of Tariffs and Dependency

Trade Wars at the Epicentre of Vulnerability….

In early 2025, the global economic landscape was jolted by the re-imposition of sweeping US import tariffs under President Donald Trump’s second administration. Framed as part of the “Liberation Day” agenda, these ad valorem duties, starting at 10%, targeted major global trading partners such as China, Mexico, and Canada. But notably, they extended across the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), including a blanket 10% tariff on all Caribbean imports to the US, with Guyana subjected to a particularly harsh 38% rate. While these measures were ostensibly intended to protect US industry, their consequences have reverberated globally.

The Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU)—comprising Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia (SLU), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG), Saint Kitts and Nevis (SKN), Montserrat, and Anguilla, sits thousands of miles from the frontlines of the US-China trade battle. Yet, in economic terms, it remains dangerously close to the epicentre. These small island economies are not merely trading partners with the US; however, they are systemically intertwined through trade, tourism, shipping, and remittance flows. The imposition of new US tariffs has added fuel to an already fragile regional structure defined by extreme import dependency, sluggish productivity, and climate exposure.

Eastern Caribbean Import Dependency in Focus….

Measured by size, the ECCU is among the smallest economic blocs in the Western Hemisphere. Yet, its structural vulnerabilities far outweigh its geographic footprint. While the economies within the union are largely services-driven, with tourism, financial services, and remittances as core pillars, they are characterized by limited industrial output, high public debt, and weak productive bases. Agriculture remains a critical yet underleveraged sector, especially in the Windward Islands, where it contributes to food security, rural employment, and export diversification. Nonetheless, the region remains heavily reliant on external markets to meet domestic consumption needs.

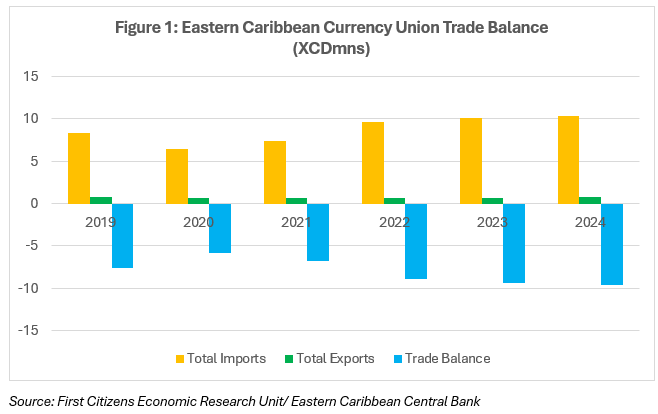

The region’s deep dependency on imports is central to its economic imbalance. According to ECCB data, trade deficits persist and are widening. Imports have steadily climbed from XCD9.6bn in 2022 to XCD10.4bn by 2024. Conversely, exports remain marginal, rising from XCD674mn in 2022 to XCD780mn in 2024 (Figure 1). The import basket is dominated by food, manufactured goods, and machinery, reflecting systemic dependency on foreign production.

ECCU Member Countries: Trade Partnerships and Imbalances

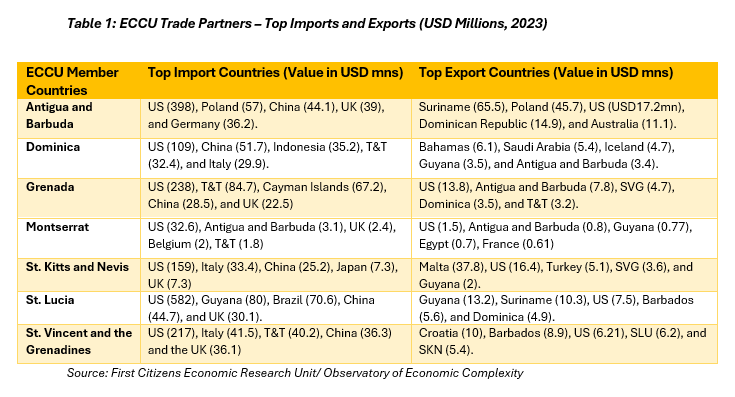

The trade relationships across the ECCU vary but exhibit common patterns of dependency. According to the most recent 2023 data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), the US remains the dominant trading partner for most ECCU member states, followed by China and the United Kingdom (UK). Other countries such as Trinidad and Tobago (T&T), Suriname, and Guyana also play significant roles in the region’s import and export activity (see Table 1).

These trade patterns emphasize the ECCU’s structural dependence on a narrow set of trading partners for both imports and exports, reinforcing the region’s vulnerability to external shocks and laying the foundation for wider issues such as food insecurity.

Food Security: A Growing Challenge

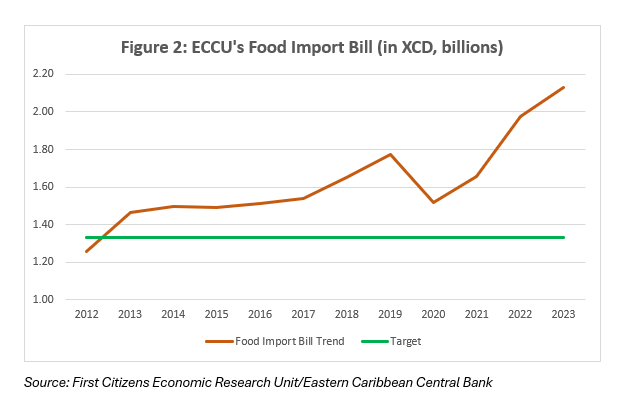

Food security is also particularly fragile. In 2019, CARICOM committed to reducing food import bills by 25% by 2025, yet this target is increasingly elusive. By 2023, seven of the eight ECCU states had registered higher food imports, with SLU and Antigua and Barbuda recording the sharpest increases and has since been steadily increasing from XCD1.8bn in 2019 to XCD2.1bn in 2023, distancing themselves from the target of XCD1.3bn (Figure 2) by 2025. This trend reflects weak domestic production, structural inertia, and fragmented policies that continue to obstruct agricultural resilience and self-sufficiency.

Tariffs, Trade and Tensions…

Tariff Transmission at a Ground Level:

Dominica:

Dominica, with an estimated GDP of approximately USD600mn, remains structurally vulnerable due to its heavy reliance on imports, particularly for essential commodities such as food, refined construction materials, and manufactured goods. A large share of these goods is sourced from the US, positioning the country at heightened exposure to US trade policy shifts, most notably tariff adjustments. This structural asymmetry renders Dominica highly susceptible to exogenous price shocks and broader global supply chain disruptions.

According to data from the Central Statistical Office (CSO) and local trade analysts, Dominica imported goods worth approximately XCD1.2bn (USD444mn) from the US between 2021 and 2024. In stark contrast, its exports to the US, mainly agricultural produce, essential oils, lotions, and artisanal crafts, stood at a mere XCD4.4mn (USD1.6mn) over the same period. Annual average exports amounted to roughly XCD1.1mn (USD400,000), highlighting a pronounced trade imbalance. While potential US tariffs pose a risk, their immediate impact on Dominican exports is expected to be muted due to stable niche demand among US diaspora communities and in the US Virgin Islands. However, greater concern lies in the rising cost of imports, particularly if third-country goods transiting through US ports become subject to new tariff regimes.

Such a development could increase prices on a wide range of imports, with significant macroeconomic implications. Dominica’s reliance on maritime transhipment through US ports for goods originating in third countries such as China and Indonesia compounds this vulnerability. For instance, according to 2023 trade data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), Dominica’s top imports included Refined Petroleum, Recreational Boats, Semi-Finished Iron, Plastic Sheetings, and Cars. These imports originated primarily from the US, China, Indonesia, Trinidad and Tobago, and Italy.

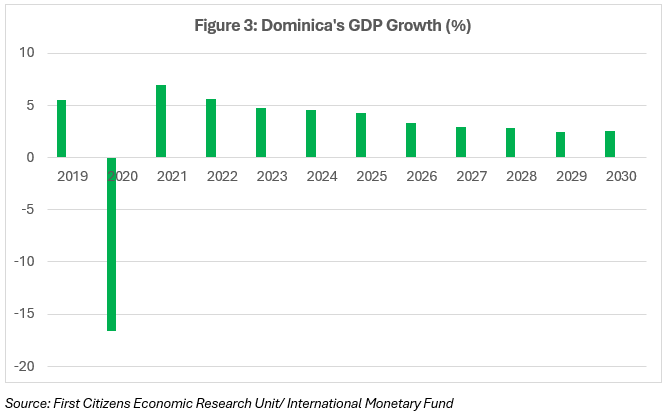

The potential cost pass-through from such tariff-induced import price hikes is particularly concerning in light of Dominica’s weakening macroeconomic trend. According to the IMF, the country’s GDP growth is projected to decelerate from 4.5% in 2024 to 4.2% in 2025, 3.3% in 2026, and approximately 2.5% by 2030 (Figure 3). Simultaneously, household purchasing power may be eroded due to imported inflation, while government fiscal space could narrow amid elevated import bills and potential subsidy demands.

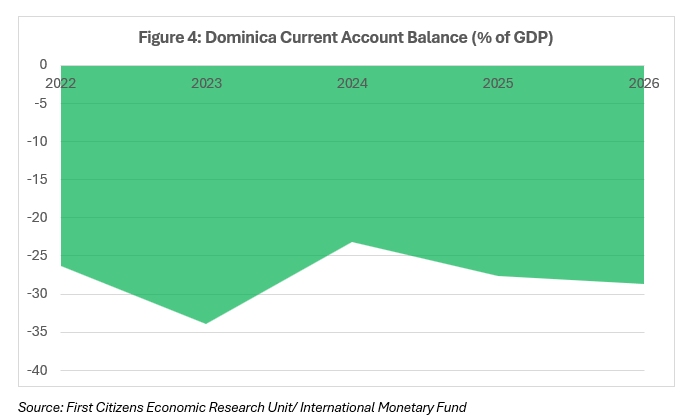

Furthermore, external imbalances remain a critical structural weakness. According to the ECCB, Dominica’s current account has consistently posted deficits, reflecting persistent trade shortfalls and reliance on external financing. After registering a deficit of 33.9% in 2023. Although it was estimated to have improved modestly to 23.2% in 2024, and is projected to rise again to 27.7% in 2025 and 28.7% (figure 4) in 2026.

In light of these long-standing vulnerabilities, Dominica’s 2024–2025 National Budget, presented pre-tariffs, outlined ambitious domestic production goals aimed at mitigating structural dependence on external markets. Chief among these were reducing poultry and meat imports by 30–40%, expanding broiler production to enhance protein security by 2030, boosting exports of fresh and processed agricultural goods, and increasing the agricultural sector’s GDP contribution to USD 700mn by decade’s end. A cornerstone of this strategy is the development of agro-processing capacity, allowing locally grown produce to be transformed into higher-value goods for both domestic consumption and export markets.

While these initiatives were conceptualized prior to recent trade policy shifts, their urgency has only intensified. With rising uncertainty around import costs and the growing risk of exogenous trade shocks, Dominica’s pivot toward self-sufficiency and value-added production presents a pragmatic macroeconomic buffer. It also signals a potential structural shift in the country’s growth model—from one reliant on consumption and imports to one anchored in production and trade resilience.

St Kitts and Nevis:

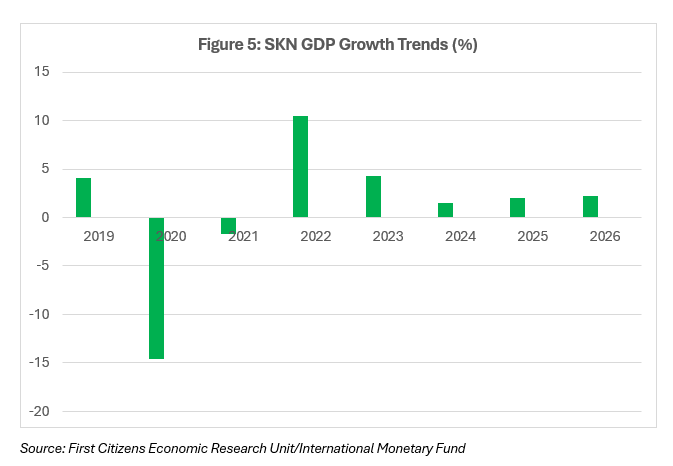

SKN, while experiencing a post-pandemic rebound with GDP growth of 4.3% in 2023, faces a deceleration in momentum as forecasts predict growth will slow to just 1.5% (Figure 5) in 2024. A modest recovery is projected, reaching 2.6% by 2030 according to the IMF. These projections reveal a vulnerable and shallow growth trend, one increasingly exposed to external shocks, especially those arising from trade-related price dynamics and geopolitical developments

SKN’s structural dependency on imports continues to pose a significant risk to macroeconomic stability. According to the latest data from the OEC, the top imports in 2023 included Refined Petroleum, Recreational Boats, Cars (USD15mn), Jewellery (USD10.2mn), and Poultry Meat. These imports originated largely from the US, Italy, China, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The composition of imports reflects not only consumer preferences and infrastructural needs but also deep integration into global—and especially US—supply chains.

Such dependence has translated into significant trade and current account imbalances. Data from the Comptroller of Customs indicate that in 2024 alone, SKN imported goods worth XCD754mn (USD 279mn) from the U.S while exporting merely XCD23.9mn (USD 8.8mn), yielding a bilateral trade deficit of over XCD730mn.

This is mirrored in the external accounts. According to the ECCB, the current account deficit (CAD) reached 11.6% of GDP in 2023 and widened further to 15.9% in 2024. Projections for 2025 and 2026 estimate CADs of 15.4% and 15.3% (figure 6), respectively. These figures highlight a persistent imbalance that will likely be exacerbated by the newly implemented US tariffs, which have begun raising the landed cost of goods in real terms.

In light of these developments, the political leadership has become increasingly vocal. Prime Minister Dr. Terrance Drew has criticized the unfairness of the US tariff regime, arguing that small island states like SKN, unlike surplus economies such as Canada or Mexico, operate under pronounced trade deficits with the US. He further pointed to the broader CARICOM–US trade imbalance, estimated at USD54bn, as evidence of a structural inequity in hemispheric trade relations. Dr. Drew has called for a more tailored and equitable US trade policy that reflects the unique vulnerabilities and asymmetries faced by small island developing states (SIDS).

Recommendation:

If there was ever a time for the Eastern Caribbean to break with old trade habits, it is now. The resurgence of US tariffs has laid bare the region’s overreliance on external markets, supply chains, and transshipment hubs. In response, policymakers must prioritize diversifying trade routes and developing regional supply networks that reduce dependency on the US market while deepening economic resilience. Examples of this shift are already emerging. Antigua and Barbuda is exploring new trade corridors through the Dominican Republic, a move that Ambassador Lionel Hurst believes could transform import logistics by bypassing costly US routes. Similarly, SVG is actively working to expand its tourism base beyond the US, with Finance Minister Camillo Gonsalves emphasizing the urgency of reducing its reliance on a single dominant source market. Meanwhile, both Dominica and SKN are exploring strategies to boost domestic production while calling for greater engagement with South and Central America, though, as Premier Mark Brantley acknowledged, logistical bottlenecks remain a pressing hurdle. These examples reflect the regional imperative: to reconfigure supply chains, strengthen direct international partnerships, and advocate for more equitable trade policies through coordinated diplomatic channels, including continued engagement with US officials and multilateral institutions like the IMF.

Conclusion:

The re-imposition of US tariffs has since emphasized a hard truth: the Eastern Caribbean remains deeply exposed to external shocks it cannot control. Yet across the region, from Dominica’s agricultural ambitions to Antigua’s trade pivot and SVG’s tourism diversification, governments are beginning to shift from reactive survival to strategic adaptation. As Premier Mark Brantley aptly put it, “All that we do here again is routed through Miami… that increases costs and makes the region vulnerable to external economic policies.” The challenge now is to turn that vulnerability into leverage—by rethinking trade infrastructure, securing new partnerships, and reducing reliance on any one market or route. This moment demands more than policy tweaks. It calls for a bold, coordinated transformation—one that repositions the EC not as a passive participant in global trade, but as a forward looking region that takes charge of its own direction.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.